Adeste fideles

translated as

Hither ye faithful

Ye faithful, approach ye

O come, all ye faithful

I. Latin: Authorship

The authorship of this Latin hymn is credited to John Francis Wade (Johannes Franciscus Wade, 1710/11–1786) on the basis of the hymn originally appearing in manuscripts signed by him. As an introduction to a detailed study of Wade’s life and work, Bennett Zon offered this summary:

He was almost certainly a convert to Roman Catholicism and attended the Dominican college at Bornhem (Belgium) where, presumably, he learnt to copy plainchant. His extant works date from 1737 to 1774 and divide into three types: plainchant manuscripts, printed books with hand-notated plainchant, and printed liturgical books without plainchant. The manuscripts, which substantially outnumber his other works, serve a wide range of functions and include Antiphonals, Graduals, Vesperals, Offices for the Dead, and books of diverse chants. Not only were they used extensively in their own time, but numerous later influential Catholic volumes were based on his work. The graphic quality of his manuscripts, often in a wide range of colours and metallic pigments, attests consistently to a scribe in complete command of his calligraphic and miniature decorative art. . . . His work in the sphere of plainchant copying and liturgical book printing represents the first concerted effort towards the revival of plainchant in England and his influence in this regard was immense.[1]

One notable account of John Francis Wade appeared in the History of St. Edmund’s College, Old Hall (1893), referring to a book of plainchant bearing an attribution to Wade on its title page, “Joannes Wade Scripsit Anno MDCCLX”:

It must have come direct from Douay. The John Francis Wade here mentioned was not a student at Douay College, but a man who made his living by copying and selling plainchant and other music. He carried on his business at Douay, simply because it was a great Catholic centre. His death is thus chronicled in the Obituary List of the Catholic Directory for 1787— “1786, Aug. 16. Mr. John Francis Wade, a layman, aged 75, with whose beautiful manuscript books our chapels, as well as private families, abound, in writing which and teaching the Latin and church song he chiefly spent his time.” The book at St. Edmunds is entirely done by hand, and is remarkable for having all the chant written on five instead of four lines. It contains all the tenebrae offices, matins, lauds, and mass for the dead, and many little pieces such as the Adeste Fideles, Rorate Coeli, the Tantum Ergo known as Webbe’s, etc. The book was used regularly until comparatively recently, and is still used occasionally.[2]

Wade was probably the son of the cloth merchant John Wade who contributed to the founding of Stourton Lodge Chapel, Stourton, and White Cloth Hall, Leeds, and he is possibly the John Wade baptized at Walton-in-Ainsty on 17 November 1710. The younger Wade is recorded as belonging to the Rosary Confraternity at Bornhem, Belgium, in 1731, where he likely received his training in calligraphy, and he is similarly recorded with the same group in Leeds, England, in 1734. Methodist scholar James T. Lightwood indicated, “in the year 1751, one John Wade was a ‘pensioner’ in the house of Nicholas King, who resided in Lancashire.”[3] A manuscript Wade produced for King is now housed at Stonyhurst College, Lancashire (see section III/E below).

Wade is believed to have lived and worked for a time in Douay (Douai), France, because of its Catholic scholasticism and favoritism toward the Jacobite cause, but Zon felt this was not representative of Wade’s total output, as two of his manuscripts are labeled “London,” dated 1750 and 1758, several others mention foreign embassy chapels in London, and the paper he used was typically either made in England or was known to have been sold in England. If Wade had spent time in Douay, it was brief.

Wade was a strong supporter of a movement to restore the family of Catholic King James II (1633–1701, the House of Stuart) to the English throne; these supporters were known as Jacobites. Jacobite symbols and messages appeared in some of Wade’s manuscripts. Zon believed “Adeste fideles” was a thinly veiled Jacobite rallying cry:

Perhaps the most startling example of Wade’s Jacobite subtexting is found in the well-known Christmas carol, “Adeste fideles,” a photograph of which appears in Stephan’s article adjacent to a chanted prayer for King James III [James Stuart, 1701–1766]. In [the Heptenstall Vesperal, 1767], “Adeste fideles” is also placed next to a prayer for the king Carolus [Charles Stuart, 1720–1788], and again in a similar position in [The Evening Office, 1773]. Given the fact that “Adeste fideles” is at times located next to prayers for the king, in combination with the incontrovertible evidence of Wade’s Jacobitism, it becomes possible to provide “Adeste fideles” with a Jacobite interpretation. Taken in this context, “Adeste fideles” combines a birth-ode and a call to arms: “Adeste fideles,” faithful draw near, or faithful be at hand! (Attention! faithful Jacobites), “laeti triumphantes,” joyful triumphant, “venite, venite, in Bethlehem,” come to Bethlehem (England), and “natum videte, regem angelorum,” see the king of angels (a pun on “regem anglorum,” king of the English, Charles Edward Stuart).[4]

At one time, the hymn was credited to John Reading (fl. 1675–1681), a view promulgated by Vincent Novello (1781–1861; see note 28), but this has been discredited and dismissed by multiple scholars because the tune cannot be found in Reading’s works and no known sources date earlier than the 1740s. Regarding the frequent labeling of “Adeste fideles” as a Portuguese hymn, see the explanation under Section V below. Bennett Zon left open the possibility of “Adeste fideles” being composed by someone other than Wade, given how the authorships of the tunes in his manuscripts were never credited, and Wade was not credited as the composer in the printed sources of the tune while he was still alive. Zon felt it was necessary to acknowledge “the possibility that Adeste was composed by someone known to Wade personally, such as Stephen Paxton or any other musician working for the foreign embassy chapels in London.”—

Implausible as it may seem, for instance, Adeste may have been composed by the same man who wrote the Missa Solemnis in G major in Cantus Diversi (1761) and the two copies of Graduale Romanum (1765), namely Thomas Arne, then organist of the Sardinian embassy chapel. This might tie together Arne’s Dublin tour of 1742–4 with the local tradition that Adeste fideles was heard for the very first time at the Dominican Channel Row Priory in Dublin around the time of the ’45 Jacobite uprising.[5]

Dom Stephan saw the composition itself as evidence of Wade’s authorship, given the unacquainted choice of wording in the Jacobite MS (Fig. 2 below), the irregular textual meter, and the gradual shift of musical meter from 3/4 to 4/4, all hallmarks of an amateur songwriter rather than a more seasoned composer like Arne:

The whole construction of the stanzas of the hymn suggests the work of a fervent tyro [novice], several of the words fitting laboriously—after a good deal of stretching—to the melody. This technical defect explains the re-writing of verses 2, 3, and 4 by the classically-minded Abbé de Borderies at the beginning of the 19th century and producing the text in use on the continent ever since. Piety, rather than mastery of the laws of prosody, distinguished Wade’s work, and far from condemning him for that, we would even praise him for his naive appealing lines. We see in it what might be called his “finger-prints,” the proof of his authorship of the hymn.[6]

II. Latin: Other Contextual Considerations

A. Nicene Creed

Regarding the underlying influences and materials of “Adeste fideles,” the second stanza borrows language from the Nicene Creed, almost verbatim, demonstrating a high regard for creedal language. The main difference is in the line “gestant puellae viscera,” where the writer has chosen pedestrian words like “gestant” (“carried”) rather than the theological “incarnatus,” and “puellae” (“maiden”) rather than “virgine.”

Nicene Creed

Deum de Deo, lumen de lumine,

Deum verum de Deo vero,

Genitum non factum, . . .

Et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto

ex Maria Virgine.

God from God, light from light,

true God from true God,

begotten not made, . . .

and is made flesh from the Holy Spirit

out of the Virgin Mary.

Adeste fideles

Deum de Deo, lumen de lumine,

gestant puellae viscera;

Deum verum, genitum non factum

God from God, light from light,

carried in the maiden’s inner parts,

true God, begotten not made.

Early copies of the manuscript use “venite adorate” in the refrain rather than the more liturgically common “venite adoremus” (see III/A below), which, taken with the verbiage above, possibly signifies the work of a layperson (like Wade), not a theologian or a priest.

B. Channel Row Dominican Priory

One longstanding tradition puts “Adeste fideles” in the Channel Row Dominican Priory, Dublin, Ireland, shortly after the failed Jacobite rebellion of 1745. In an article in 1915, W.H. Grattan Flood mentioned, “we cannot find [the tune] associated with “Adeste Fideles” earlier than the year 1746, in which year it was sung in the Convent Chapel of the Dominican Nuns of Dublin.”[11] How he came about this information is unclear, but a member of that Dominican community independently confirmed the authenticity of the story:

Dr. Grattan Flood’s statement about the Adeste being first sung in our Chapel in 1748 [sic] is quite authentic, though it does not appear from the Annals where the nuns got the music from. As the Channel Row Convent was a centre of ecclesiastical life—there were no fewer than three Bishops consecrated in the Convent Chapel—there was constant contact with Douay, whither young priests and ecclesiastical students travelled fairly constantly, so that it is possible that the Adeste came by that channel. . . . It is very probable that J.F. Wade was a visitor in Channel Row and possibly the MSS in question (of the Adeste) came through him. The nuns lived there and braved the fearful persecution of 1745, and actually had priests and bishops in hiding many times during those dreadful years.[12]

C. Charles-Simon Favart, “Rage inutile”

The proper dating of the composition of “Adeste fideles” relies in part on the Jacobite allusions in the earliest manuscripts, and some scholars have wondered whether the chant tune was used as the basis for a French parody, which has a firm date of composition. This hypothesis works, in part, because of Wade’s apparent ties to French Catholicism. Early in the 20th century, G.E.P. Arkwright had noticed how the first eight measures of “Adeste fideles” were similar to a song from a French comic opera, Acajou, by Charles-Simon Favart (1710–1792), which had premiered at the Théâtre de la Foire, Paris, on 18 March 1744.[7] The song “Rage inutile,” which was labeled in the libretto as using an “Air Anglois” (“English air”) was first published in the revised 1748 score for the opera (Fig. 1). Whereas Arkwright wondered whether “Adeste fideles” and “Rage inutile” shared a common English folk tune ancestry, Dom John Stephan hinted toward the French melody being a direct parody of “Adeste fideles.”[8] Bennett Zon took this idea farther, suggesting the French song was not just a parody of “Adeste fideles” but also a parody of the Jacobite movement at large:

Certainly, there are key words in Favart which signify parody, and as Stéphan asserts, the activities and attitudes of Jacobites and Charles Edward would have been known to the French at large by 1743 and were an easy target for political satire. In this way certain aspects of “Rage inutile!” come alive with political subtext and parallels with Adeste.[9]

Lutheran scholar Joseph Herl was less convinced by the theory and offered an important reality check:

This [process of transmission] appears plausible, given that “Rage inutile” did not appear until 1748 . . . But because “Rage inutile” and “Adeste fideles” have only the first phrase and a few more notes in common with each other, it is also possible that the resemblance is simply a coincidence and that neither was derived from the other.[10]

Fig. 1a. Acajou Opera Comique en Trois Actes (1748). The melody is printed on a French violin clef, where the bottom line is G (notice how the clef circles the bottom line), with sharps for D major on C and F.

Fig. 1b. Acajou Opera Comique en Trois Actes (1748).

III. Latin: Manuscripts

A. Maurice Frost Jacobite MS (1740s), pp. 93–95

This manuscript, likely to be the oldest of those listed here, was formerly held by the Vere Harmsworth Library, Oxford, England, sold at auction for unknown reasons in 1946, and purchased by esteemed English scholar Maurice Frost (1888–1961). Frost loaned it to Dom John Stephan of the Order of Saint Benedict, who examined it in detail and photographed five pages for reproduction in his published study (1947 | Fig. 2). The title page had been removed, which would have included Wade’s signature and date, but Stephan was able to confirm it as Wade’s work. It contained a chanted prayer beginning “Domine salvum fac Regem nostrum Jacobum” (“Lord, make safe our King James”), most likely a reference to James Francis Edward Stuart (James III, “The Old Pretender,” 1688–1766), the contested Catholic king of England. From this reference, Stephan believed the manuscript was prepared before the unsuccessful Jacobite uprising in 1745, but this alone does not logically limit the date of writing, as James III lived to 1766 and Wade’s Jacobite allegiances did not end in 1745.

Fig. 2. Jacobite MS, reproduced in Dom John Stephan, Adeste Fideles (1947).

A better argument for this manuscript’s position as the oldest known source for “Adeste fideles” is in the way the refrain in this copy begins “Venite adorate” (“Come, adore”) rather than the more liturgically common phrase, “Venite adoremus” (“Come, let us adore”). Stephan explained, “This formula, therefore, seems to brand the writer of the first Adeste as an inexperienced layman teaching Latin to boys, and anxious to co-ordinate his grammatical rules, but not quite familiar with the deeper requirements of a public prayer. This oversight must have been pointed out to him by a more competent person . . .”[13]

In the Jacobite MS, notice in the first stanza the double bar and “Rep” before “Natum,” and similar figures in the other stanzas. In later editions of the hymn, this would come to be more clearly understood as a repeat of the second half of each stanza. Also worth noting in the Jacobite MS is the construction of the tune in a triple meter. In this notation, a square is one beat, a diamond is half a beat, and a stemmed note is two beats, with dots acting as they do in modern notation.

The present location of the Jacobite MS is unknown. Keyte and Parrott (1992) referred to it as the Douai MS, either reflecting a mischaracterization of the provenance of Frost’s MS, or a possible landing spot for it after his death. Bennett Zon (1996) claimed it was “no longer extant” without explanation.

B. Conglowes Wood College MS (1746)

W.H. Grattan Flood reported the existence of a manuscript made by Wade once belonging to the Museum of Clongowes Wood College, Kildare, Ireland, dated 1746. Grattan Flood said this manuscript was “almost exactly the same” as source D.[14] In an attempt to examine this copy for his 1947 publication, Stephan reported the manuscript “had been in possession of the College for perhaps 200 years, but has recently ‘been lost or stolen’ from the library.”[15] The current location of the manuscript is unknown.

C. University of Glasgow, GB 247 MS Euing R.d.90^2, pp. 48–50 (1750)

One of two surviving manuscripts from 1750, this one is held at the University of Glasgow, Archives & Special Collections, GB 247 MS Euing R.d.90^2, formerly belonging to the Royal College of Science and Technology, a successor of Anderson’s College, to whom the manuscript had been bequeathed by William Euing in 1874. The title page reads in part, “Modus intonandi Gloria Patri in fine Introitus per Octavos Tonos” (“The method of intoning the Gloria Patri at the end of the Introit using the eight tones”) with the attribution “Joannus Franciscus Wade scripsit. 1750.” Like the Jacobite MS, the music is in triple time, the stanzas have a half-repeat, and the refrain reads “Venite adorate” rather than the later “Venite adoremus.”

Fig. 3. University of Glasgow, Archives & Special Collections, GB 247 MS Euing R.d.90^2.

D. Durham University, Vesperale Novum (1750)

This manuscript is titled Vesperale Novum (“New Vesperal”), dated 1750. According to Zon, this version of the melody is in triple time, like sources A and C (and by Grattan Flood’s testimony, like source B). This manuscript was previously housed at the Convent of Poor Clares, Woodchester, Gloucestershire, England; in 2011 this community merged with the Convent of Poor Clares at Lynton, North Devon, at which time the Woodchester manuscript was transferred to Durham University.

E. Stonyhurst College, Cantus Diversi (1751), MS C vii 7, pp. 181–183

This manuscript, titled Cantus Diversi and dated 1751, is held in the Archives of Stonyhurst College, Lancashire, England (Fig. 4). According to Grattan Flood, it was made on behalf of Nicholas King.[16] J.T. Lightwood corroborated this connection, saying, “in the year 1751, one John Wade was a ‘pensioner’ in the house of Nicholas King, who resided in Lancashire.”[17] This copy, like other earlier copies, has the asterisk/double-bar repeat in each stanza, and it is in a triple meter, but here the refrain had been revised to say “Venite adoremus.” A single page of this manuscript was reproduced by Stephan in his 1947 study (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Stonyhurst College, MS C vii 7 (Cantus Diversi, 1751), reproduced in Dom John Stephan, Adeste Fideles (1947).

Regarding the kingly prayer in this manuscript, Stephan noted:

The Stonyhurst copy . . . has the name altered to JOSEPHUM, which can be explained by the likely supposition that this particular copy, . . . was written for the benefit of the English College at Lisbon, where King John V had died in that year and was succeeded by his son Joseph. The loyalty of the English students abroad was now transferred to the King of the country where they resided, since there was no longer any hope of the Pretender’s return to England.[18]

Although the connection to Portugal’s King Joseph I (or José I, reigned 1750–1777) is likely correct, the connection to the English College at Lisbon is probably a misunderstanding by Dom Stephan. Bennett Zon noted how Wade’s works, and this manuscript in particular, were often connected to the chapels of the foreign embassies in London, including the Portuguese chapel:

A number of his manuscripts, including Cantus Diversi (1749, 1751, 1761), Graduale Romanum (two of 1765) and Kyriale (n.d.), contain Masses with foreign embassy chapel headings, such as Missa Sardónica, Missa Hyspánica, Missa Itálica, Missa Portugállis, and rather strangely, Missa Polónica. Cantus Diversi (1751), moreover, supplies not only several embassy chapel headings but the subheadings “In Ecclésia Hyspánica & Sardínica” in the Kyrie of [Missa] In Domínicis per Annum and “Hisp. & Sard. Cantátur” in the Agnus Dei of Missa B Maríae V.[19]

For more on the associations of this hymn with the Portuguese chapel in London, see the discussion below in sections IV/B and V.

F. Smith College Libraries, Vesperale Novum (1754), Rare Book 783.2 V636

One of Wade’s manuscript copies of “Adeste fideles” is held or was formerly held by the Smith College Libraries (Northampton, Massachusetts), Mortimer Rare Book Collection, 783.2 V636, titled Vesperale Novum (1754). In this codex, like those preceding it, the melody was written in triple time. Very little information about this copy is currently available. [Special Collections staff has disavowed any knowledge or record of this MS, Dec. 2020]

G. Pitts Theology Library, Emory University, Graduale Romanum pro Dominicis et Festis per Annum (1756), MSS 072

This copy was formerly held by the Virtue and Cahill Library, Portsmouth, England; the collection was relocated during World War II then apparently divided and sold at auction in 1967. This Graduale Romanum has Wade’s inscription in the front, dated 1756. The rhythm here is in duple time, in contrast to the earlier examples in triple. It has four stanzas.

Fig. 5. Emory University, Graduale Romanum pro Dominicis et Festis per Annum (1756), MSS 072.

H. Pitts Theology Library, Emory University, Vespertinus pro Dominicis et Festis per Annum (1757), MSS 073

Like copy G above, this one was acquired from the former Virtue and Cahill Library, Portsmouth, England, after World War II. It has a title page with Wade’s inscription, and it is dated 1757. The rhythm in this one different yet again from the one before it. Rather than being grouped into duples or triples, the notes are separated by each word, making the intended metrical emphasis difficult to discern. Wade clearly struggled with this aspect of composition.

Fig. 6. Emory University, Vespertinus pro Dominicis et Festis per Annum (1757), MSS 073.

I. St. Edmund’s College, Antiphonae et Lamentationes Jeremiae (1760), pp. 207–208

St. Edmund’s College, Ware, England, holds more than one Wade manuscript. “Adeste fideles” is included in the codex titled Antiphonae et Lamentationes Jeremiae (1760). According to Zon, this copy is like H in the way “the tune loses most of its diamond notes and rhythmic accentuation. Words are grouped regardless of syllabic emphasis, though accented syllables are often musically notated with tailed square notes corresponding to textual accents. Slight differences in the tune have also crept in, these being most noticeable at its cadence.”[20] Hugh Keyte and Andrew Parrott, writing for the New Oxford Book of Carols (1992), also observed the strange shift in Wade’s composition:

The first version is in clear triple time. Subsequent versions exhibit metrical/notational differences. Moreover, changes in notation in Wade’s later manuscripts often appear arbitrary. These versions frequently depart from the notation of identical plainchant given in contemporary English Catholic plainchant treatises such as The Art of Singing (Thomas Meighan, 1748) and The True Method to Learn the Church Plain-Song (James Marmaduke, London, 1748). The 1760 version, for example, has a refrain that entirely resists duple or triple classification.[21]

The first page of this manuscript was reproduced in Stephan’s 1947 study (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. St. Edmund’s College, Antiphonae et Lamentationes Jeremiae (1760), reproduced in Dom John Stephan, Adeste Fideles (1947).

J. St. Edmund’s College, Graduale (1760)

Another manuscript at St. Edmund’s College, Ware, England, is a Graduale, dated 1760. Dom Stephan reproduced one page for his 1947 study (Fig. 8). From this, we see this and source I (also 1760) have nearly identical rhythms, no longer a triple feel, and yet not conforming to a steady duple meter. As Zon put it, “From this sarabande triple-time version the tune begins its rather awkward development towards duple-time.”[22] Notice especially how the barlines no longer represent groups of three beats, they represent divisions of words. The calligraphic style of J is slightly different than I, with smaller notes and a less ornate drop-cap “A,” but still recognizable as Wade’s hand.

Fig. 8. St. Edmund’s College, Graduale (1760), reproduced in Dom John Stephan, Adeste Fideles (1947).

The Graduale and the Antiphonae, both being made in 1760, were probably intended to be used together by the same community. In fact, Zon believed both were probably made for “the Sardinian embassy chapel, whose liturgical books were destroyed in a 1759 fire.”[23] Moreover, Zon identified cross references between the two. Their current home, together in the same library, is fortunate and appropriate.

K. Stanbrook Abbey Archives, Cantus Diversi (1761)

Bennett Zon (1996) indicated this manuscript contained Masses intended for the foreign embassies of London. The codex was formerly in the possession of St. Mary’s Priory, Fernham, Oxfordshire, England. Due to dwindling numbers, they sold the property in 2002/3 and their archives were moved to St. Mary’s Abbey, Colwich, Staffordshire. In turn, for similar reasons, this community and its archives merged into Stanbrook Abbey, Wass, North Yorkshire in 2020.

L. St. Edmund’s College, Heptenstall Vesperal (1767)

The third Wade manuscript in the possession of St. Edmund’s College, Ware, England, is the Heptenstall Vesperal (1767). Zon described the manuscript as being bound with The Evening-Office (1760), a printed volume, uncredited, but also thought to be by Wade. The melody of this copy is substantially the same as in the 1760 manuscripts at St. Edmunds (sources G, H).[24] The manuscript contains a prayer for king Carolus, who could be Charles Edward Stuart of England (1720–1788), the disputed heir to the British throne after the death of his father in 1766, or it could be Charles Emmanuel III (1701–1773), king of Sardinia. [MS reported missing/lost, 2019]

Pseudo-Wade MSS

M. Henry Watson Music Library, Cantus Diversi (1760s), BR M350 Hz 53

This manuscript at the Henry Watson Music Library, part of the Manchester Central Public Library, is titled Cantus Diversi, undated. According to Zon, “Stephan attributes this to Wade, but it is probably a copy of a Wade manuscript by another scribe.”[25] The first page of “Adeste fideles” was reprinted by James T. Lightwood (Fig. 9). In this copy, notice the English heading (versus Wade’s usual Latin), the absence of the key signature (the flatted notes are individually marked), some rhythmic variants, and the notes were left unfilled. The barlines separate the words rather than indicating time, a feature consistent with Wade’s manuscripts from 1760. The double bar marks the inner-stanza repeat, but it lacks the other signifiers, like the asterisk or instruction “Rep.”

Fig. 9. Henry Watson Music Library, Cantus Diversi, BR M350 Hz 53, reproduced in J.T. Lightwood, The Music of the Methodist Hymn Book (1935).

N. Library of Congress, Cantus Diversorum (1758), M 2147 XVIII M2

This manuscript, held by the U.S. Library of Congress, Washington D.C., is known as the Cantus Diversorum (1758). The main body of the codex is by Wade, but according to Zon, “Adeste fideles is found in a section of the manuscript almost certainly copied by a scribe other than Wade after J.P. Coghlan’s first publication of An Essay on the Church Plainchant (1782),”[26] meaning the form of the melody in this manuscript reflects the printed version of 1782 rather than Wade’s handwritten copies.

IV. Latin: Publication

A. The Evening Office of the Church (1760 / 1773)

“Adeste fideles” was first published in The Evening Office of the Church, in Latin and English, Containing the Vespers or Even-Song, for All Sundays and Festivals of Obligation (1760), text only, in four stanzas. It appeared in parallel columns in Latin and prose English, the English translation being somewhat loose (see “Dominum” versus “Three in One,” for example). This collection is believed to have been produced by Wade, in part because the 1773 edition was clearly labeled “Printed for J.F.W.” The 1760 edition has similarities to the two 1760 manuscripts (I, J), such as being labeled as a Prose for the Nativity, appointed for the Benediction. Notice also the asterisks in the text marking the repeats. If Wade was indeed the producer of the 1760 edition, as he seems to have been, then he had the distinction of not only producing his own manuscripts, but putting his hymn into print for the first time and providing the first published English translation.

In the Proses section of the book, under “The Litanies of the Blessed Virgin Mary,” Wade included the kingly prayer, “Domine salvum fac Regem nostrum, N,” apparently intended to be left open for whomever might be king at the time (“Nomine” = “Name”), rather than his habit of naming the reigning monarch.

Fig. 10. The Evening Office of the Church, in Latin and English (1760).

The 1773 copy is substantially the same, minus the appointment for Benediction. The title page, while mostly the same, included a cryptic message. Zon decoded the sequence to read “Quos anguis Tristi diro cum vulnere Stravit hos sanguis Christi miro Tum munere lavit” (“Those whom the snake lays low with a sad dread wound are with the blood of Christ washed afterward with a wonderful gift”). He saw in this a possible Jacobite double-meaning:

From a Jacobite standpoint various aspects of this can be interpreted as follows: “Those whom the snake lays low,” English Catholics; the “snake,” George III and the Hanoverian throne; the “sad dread wound,” persecution; “Christ,” Charles Edward Stuart; and “a wonderful gift,” the restoration of the Stuart throne.[27]

On page 345, Wade included the kingly prayer, “Domine salvum fac Regem nostrum, N,” again avoiding any particular name.

Fig. 11. The Evening Office of the Church, in Latin and English (1773).

B. Samuel Webbe (1782 / 1792)

The first two musical appearances of “Adeste fideles” in print were in publications edited and arranged by Samuel Webbe (1740–1816). As organist of the Sardinian and Portuguese embassies, Webbe would have been familiar with Wade’s manuscripts and possibly knew him personally. Webbe included “Adeste fideles” in An Essay on the Church Plain Chant, Part Second (London: J.P. Coghlan, 1782 | Fig. 12), using all four stanzas, arranged in two parts (melody and bass, C-clef and F-clef). In spite of being labeled “G major,” the music was notated in F major. Notice also a feature of the arrangement still common more than two centuries later: the melody of the refrain (“Venite adoremus”) begins on its own, then is joined in the next phrase by the second voice entering on the tonic while the melody jumps up to the third. Most importantly, Webbe regularized Wade’s melody into a proper duple measure, a musical journey nearly four decades in the making (stemmed squares here are worth two unstemmed).

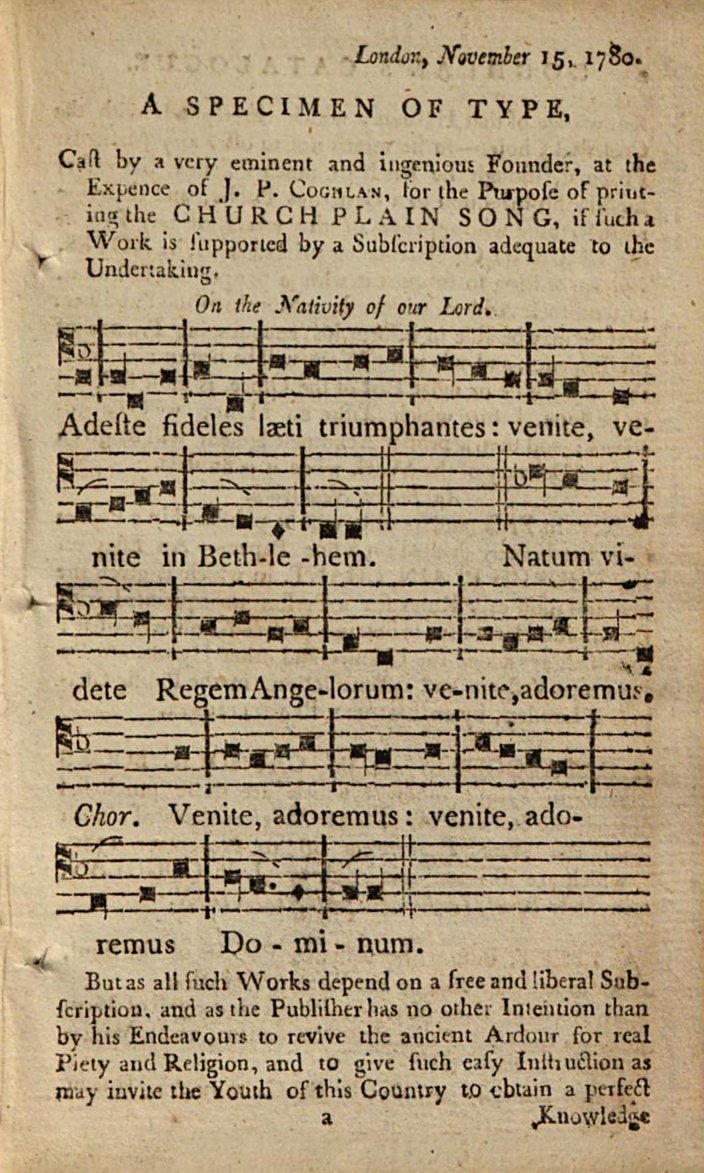

A preview of this publication was given in The Laity’s Directory . . . for the Year of Our Lord MDCCXXXI (London: J.P. Coghlan) on a page dated 15 Nov. 1780, in which the publisher asked for financial subscribers to help fund the production of Webbe’s forthcoming book of church plainsong. In this preview, the melody was printed on a five-line staff, versus the four-line staff in the eventual product, with only one stanza of the text.

Fig. 12a. The Laity’s Directory for 1781.

Fig. 12b. An Essay on the Church Plain Chant, Part Second (London: J.P. Coghlan, 1782).

Webbe published “Adeste fideles” again ten years later in A Collection of Motetts or Antiphons (London: T. Jones, 1792 | Fig. 13), this time in a four-part arrangement. The way the score is written, a soloist sings each stanza and refrain, then a chorus enters and repeats the last phrase of the stanza and the refrain. Here again, the refrain is built cumulatively, starting with the melody, adding the alto a third below, then joined by the tenor and bass. In hymnody, this style of part writing is called a “repeating tune” or a “fuguing tune,” but it is not technically a fugue in the standard baroque sense.

Fig. 13. A Collection of Motetts or Antiphons (London: T. Jones, 1792).

V. Portuguese Hymn

In spite of being circulated for fifty years in manuscript and in print, “Adeste fideles” seems to have escaped the notice of the general English public, possibly owing to the suppressed status of the Catholic community in England and the hymn’s limited performance within foreign embassies. The catalyst for its explosion in popularity was its use at the Portuguese embassy chapel, where Samuel Webbe was organist. By one account, in 1795, the Duke of Leeds, Francis Godolphin Osborne (1751–1799) had attended a service at the chapel and was enamored by “Adeste fideles.” According to Keyte and Parrott—

[“Adeste fideles”] made such an impression on the Duke of Leeds that he commissioned an arrangement from Thomas Greatorex, director of the popular “Concerts of Antient Music,” of which the Duke was a patron. The arrangement was in B-flat, for SATB soloists, choir, and orchestra, and was first performed at one of these concerts on 10 May 1797; it was repeated on many subsequent occasions, making the hymn famous far beyond the Catholic circles to which it had been initially confined.[28]

Two surviving manuscript copies of the Greatorex arrangement are housed at the Royal College of Music, RCM MS 672/2 and RCM MS 670/3, both labeled “Portuguese Hymn.”

From the influence of this arrangement and the Concerts of Antient Music, the tune was then rapidly picked up by many others. It was published as sheet music, ca. 1798–1799, through multiple printing houses, titled “Adeste Fideles: The Favorite Portugueze Hymn on the Nativity,” for voices and piano (Fig. 14), together with “The Sicilian Mariner’s Hymn” (“O Sanctissima”).

Fig. 14. “Adeste Fideles: The Favorite Portugueze Hymn on the Nativity” (London: Goulding & Co., ca. 1799).

“Adeste Fideles” made its first appearance as a hymn tune in two collections in 1799: Second Volume to the Rev. Dr. Addington’s Collection of Psalm and Hymn Tunes (London: T. Conder & C. Logan, 1799), where it was called PORTUGUESE and set to the text “How glorious the lamb is seen on his throne,” from George Whitefield’s Collection of Hymns (1753); and Peck’s Collection of Hymn Tunes (London: J. Peck, 1799 | Fig. 15), called PORTUGAL NEW and set to the text “Oh, praise ye the Lord; prepare a new song,” by Philip Doddridge.

Fig. 15. Peck’s Collection of Hymn Tunes, Book 1 (London: J. Peck, 1799). Melody in the tenor part.

After 1799, variants of Wade’s tune were then printed 260 times within the next 20 years in collections of English hymn tunes, but almost never with the original Latin text or an English translation, typically conscripted to fit the texts of other hymns.

In the United States, “Adeste fideles” was first published in Benjamin Carr’s Musical Journal, vol. 1, no. 29 (29 Dec. 1800 | Fig. 16).[29] Carr’s edition was headed “The celebrated Portuguese Hymn for Christmas Day with an English Translation,” given in three stanzas of Latin and English (minus Wade’s st. 2), the English beginning “Hither ye faithful, haste with songs of triumph.” This edition included the half-way repeat before the refrain (like Fig. 11 above). Carr’s translation proved to be fairly popular, appearing in 33 other music collections through 1820, then in dozens of other collections over the next two centuries, now preserved mostly through shape-note tune books, as recently as An American Christmas Harp (2009).

Fig. 16. Musical Journal, vol. 1, no. 29 (29 Dec. 1800).

VI. Latin: Additional Text

During the unrest of the French Revolution, Étienne Jean François Borderies (1764–1832), a Catholic priest, took refuge in London in 1793. While in London, he came into contact with “Adeste fideles” and took it back with him to France in 1794, where he would later become vicar of the St. Thomas d’Aquin church in Paris (1802), vicar general over the diocese of Paris (1819), and bishop of Versailles (1827). Borderies wrote three new stanzas for the hymn as replacements for Wade’s last three; these were first printed in Office de Saint Omer (1822 | Fig. 17), uncredited, text only.

As a matter of poetry, this text is metrically regular (12.10.11 plus refrain), compared to Wade’s, in which no two stanzas are the same. Thematically, the second stanza covers the call of the shepherds to hasten to the manger and rejoice; the third explains how they (we) will see the splendor of the eternal Father robed in flesh, the child-God wrapped in cloth; the fourth speaks of embracing the poor child in the hay and asks, how could we not love the one who loves us?

Fig. 17. Office de Saint Omer (Saint Omer: Pastre et Baclé, 1822).

One other stanza has made its way into the canon, an anonymous text, first known to have been printed in the Thesaurus Animae Christianae (Mechelin: Dessain, 1857), describing how, with the star as a guide, the Magi have come to worship the Christ, bringing gold, frankincense, and myrrh as gifts; our hearts are made child-like by Jesus:

Stella duce Magi Christum adorantes,

Aurum, thus et myrrham dant munera;

Jesu infanti corda praebeamus.

In French collections, this stanza is often inserted into Borderies’ text as the third stanza.

VII. English Translations

A. Frederick Oakeley et al.

The origins of the translation by Frederick Oakeley (1802–1880), “Ye faithful, approach ye,” were first reported by Josiah Miller in 1869, writing briefly, “He has kindly informed us that he wrote his translation when he was at Margaret Chapel, about 1841.”[30] Oakeley had been trained at Oxford and served in the Church of England, including Margaret Street Chapel (rebuilt as All Saints’ Church, Margaret Street, 1850–1859), until he resigned his position in 1845 to convert to Catholicism. The earliest publication is not well documented, but it appeared as early as 1846 in Sacred Hymns and Anthems (Leeds: G. Crawshaw, 1846 | Fig. 18).

Fig. 18. Sacred Hymns and Anthems (Leeds: G. Crawshaw, 1846).

Oakeley’s translation is based on Wade’s original four stanzas, and like the original Latin, this translation is metrically irregular. In the second stanza, Oakeley followed Wade’s example by using text verbatim from the Nicene Creed rather than trying to fill the meter. In the third line, “Lo, He abhors not the Virgin’s womb,” he took Wade’s “gestant puellae viscera” (“carried in the maiden’s inner parts”) and enriched the text with venerable language from the Te Deum, which reads “non horruisti Virginis uterum” (“you did not abhor the virgin’s womb”). In its original context, the line was a rebuttal of gnosticism, in which the divine does not intermingle with corrupt flesh, therefore gnostics believed Jesus could not have been human.

Oakeley’s text has been better known through a revision made for A Hymnal for Use in the English Church (London: John & Charles Mozley, 1852 | Fig 19), edited by Francis H. Murray (1820–1902). Murray’s version introduced the opening line “O come, all ye faithful,” and this version, like Oakeley’s original and the Latin, is metrically irregular. Murray’s changes to the third stanza, “Sing all ye powers of heav’n above,” etc., have not been as widely adopted as his improved opening line.

Fig. 19. Hymnal for Use in the English Church (London: John & Charles Mozley, 1852).

When this hymn was adopted into Hymns Ancient & Modern (1861 | Fig. 20a), editor Henry Baker (1821–1877) used Oakeley’s text as a basis, substituted Murray’s first line, and tweaked “Joyful and triumphant,” and “Now in flesh appearing.” The arrangement by William Henry Monk (1823–1889) has been repeated in many other collections, especially the revised version from the 1875 edition (Fig. 20b).

Fig. 20a. Hymns Ancient & Modern (London: Novello, 1861).

Fig. 20b. Hymns Ancient & Modern (London: William Clowes & Sons, 1875).

Some hymnological sources claim a measure of influence for William Mercer (1811–1873) and his revision of Oakeley’s text in the Church Psalter & Hymn Book (1855; preface Dec. 1854), but in reality, Mercer’s text, aside from a few lines in common with Oakeley/Murray, is mostly new and mostly forgettable, not worth repeating here (digital copies are easily available). His claim on the annals of history is in the way he tried to fill the meter of the second stanza. This not unique, however, as John Julian (1892) listed fourteen other attempts to rephrase the same lines. Although a congregation is generally aided by having a consistently metrical text to sing, hymnologist Erik Routley—in his usual acerbic style—felt the various attempts to fix the meter were overblown:

Other translations have appeared, which often attempt to fit the tune more exactly syllable for syllable, and the Church Hymnary (1927) actually prints the translation of William Mercer alongside that of Oakeley: this only gives us the opportunity of judging how abysmally prosaic an author who tried to be poetically consistent could become. Dissenters, for some reason, always sing in verse 2 the clumsy expression “True God of true God, Light of light eternal,” which spoils the effect of “Very God” at a later point in that verse. There is little sense in doing this, except if you refuse on principle to learn to sing Oakeley correctly.[31]

B. William T. Brooke

The first notable attempt at publishing all eight stanzas in English was made by the editors of The Altar Hymnal (words only, 1884; with music, 1885 | Fig. 21), using a composite of Frederick Oakeley (sts. 1–2, 7–8) and William T. Brooke (1848–1917; sts. 3–6). In Latin, the underlying stanzas would be Wade (1–2), Borderies (3), anonymous (4), Borderies (5–6), and Wade (7–8). In this hymnal, the text was misattributed to John Reading (based on the faulty testimony of Vincent Novello); the harmonization was by Arthur Henry Brown (1830–1926).

Fig. 21. The Altar Hymnal (London: Griffith, Farran, Okeden & Welsh, 1885).

This version from The Altar Hymnal has found a longer life through the editorial touch of Percy Dearmer (1867–1936), editor of The English Hymnal (1906 | Fig. 22). In this case, Dearmer used Oakeley/Murray/Baker for stanza 1, Oakeley for 2, a revision of Brooke for 3 through 5, Oakeley for 6, and Oakeley/Baker for 7. He omitted Brooke’s “There shall we see Him” (Borderies’ “Aeternae parentis,” etc.). With the text still being irregular, singers must learn how to place the syllables among the notes. Subsequent hymnal editors, not being content to let irregularities go untouched, have continued to make minor adjustments. Dearmer’s version has been repeated in other collections. The harmonization is essentially the same as William Henry Monk’s arrangement from 1875, but reclaiming the bass suspension in the fifth chord from 1861.

Fig. 22. The English Hymnal (Oxford: University Press, 1906).

For another full translation of all eight Latin stanzas, see the version by Ronald A. Knox (1888–1957) in The Westminster Hymnal (1940). For his version, Knox borrowed the first stanza from Oakeley/Murray/Baker and some other lines from Oakeley, but otherwise went a long way toward providing an accurate rendition of the Latin in a predominantly regular meter. Nonetheless, his version has not been widely adopted. With the mixed-meter versions being so deeply ingrained in the popular vernacular, it seems unlikely that any consistently metrical renditions will ever overtake a beloved Latin text born in irregularity.

For a textual-devotional analysis of the Oakeley/Murray translation, see Albert Edward Bailey (1950) or Robert Cottrill (2012).

by CHRIS FENNER

for Hymnology Archive

30 November 2020

rev. 29 October 2022

Footnotes:

Bennett Zon, “The Works of John Francis Wade,” The English Plainchant Revival (1999), p. 104.

Bernard Ward, History of St. Edmund’s College, Old Hall (London: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1893), p. 142 (Archive.org), citing James Peter Coghlan’s Laity’s Directory for 1787, and Samuel Webbe’s “Tantum Ergo” tune in An Essay on the Church Plain Chant, Part Second (London: J.P. Coghlan, 1782).

James T. Lightwood, Hymn Tunes and Their Story (London, C.H. Kelly, 1905), p. 156: Archive.org

Bennett Zon, “The Works of John Francis Wade,” The English Plainchant Revival (1999), p. 138.

Bennett Zon, “The origin of Adeste Fideles,” Early Music, vol. 24, no. 2 (May 1996), pp. 282–283; see also Hugh Keyte & Andrew Parrott, “Adeste Fideles,” New Oxford Book of Carols (1992), p. 242.

Dom John Stephan, The Adeste Fideles: A Study on Its Origin and Development (1947), p. 21.

G.E.P. Arkwright, “Notes and Queries,” The Musical Antiquary, vol. 1 (April 1910), pp. 188–189: HathiTrust

Dom John Stephan, The Adeste Fideles: A Study on Its Origin and Development (1947), pp. 9, 20.

Bennett Zon, “The origin of Adeste Fideles,” Early Music, vol. 24, no. 2 (May 1996), pp. 287–288.

Joe Herl, “O come, all ye faithful,” Lutheran Service Book Companion to the Hymns, vol. 1 (2019), p. 133.

W.H. Grattan Flood, “Notes on the history of ‘Adeste Fideles,’” The Musical Times, vol. 56, no. 868 (June 1915), p. 361: JSTOR

S.M. Peter, O.P., Prioress, quoted in Dom John Stephan, The Adeste Fideles: A Study on Its Origin and Development (1947), p. 9

Dom John Stephan, The Adeste Fideles: A Study on Its Origin and Development (1947), p. 21.

W.H. Grattan Flood, “Notes on the history of ‘Adeste Fideles,’” The Musical Times, vol. 56, no. 868 (June 1915), p. 361: JSTOR

Dom John Stephan, The Adeste Fideles: A Study on Its Origin and Development (1947), p. 4.

W.H. Grattan Flood, “Notes on the history of ‘Adeste Fideles,’” The Musical Times, vol. 56, no. 868 (June 1915), p. 361: JSTOR

James T. Lightwood, Hymn Tunes and Their Story (London, C.H. Kelly, 1905), p. 156: Archive.org

Dom John Stephan, The Adeste Fideles: A Study on Its Origin and Development (1947), pp. 19–20.

Bennett Zon, “The origin of Adeste Fideles,” Early Music, vol. 24, no. 2 (May 1996), p. 281.

Bennett Zon, “The origin of Adeste Fideles,” Early Music, vol. 24, no. 2 (May 1996), pp. 281–282.

Hugh Keyte & Andrew Parrott, “Adeste Fideles,” New Oxford Book of Carols (1992), p. 243.

Bennett Zon, “The origin of Adeste Fideles,” Early Music, vol. 24, no. 2 (May 1996), p. 281.

Bennett Zon, “The Works of John Francis Wade,” The English Plainchant Revival (1999), p. 119.

Bennett Zon, The English Plainchant Revival (1999), p. xx.

Bennett Zon, “The origin of Adeste Fideles,” Early Music, vol. 24, no. 2 (May 1996), p. 281.

Bennett Zon, “The origin of Adeste Fideles,” Early Music, vol. 24, no. 2 (May 1996), p. 281.

Bennett Zon, “The Works of John Francis Wade,” The English Plainchant Revival (1999), p. 137.

Hugh Keyte & Andrew Parrott, “Adeste Fideles,” New Oxford Book of Carols (1992), p. 242; Vincent Novello (1781–1861), who succeeded Webbe as organist of the Portuguese chapel, gave a version of this story in The Congregational and Choristers’ Psalm and Hymn Book (1843 | Google Books), p. 14, and attributed the words to John Reading, 1680; see also Mary Cowden Clarke, The Life and Labours of Vincent Novello (London: Novello & Co., 1864), p. 5: Archive.org

Both Precht (1992) and Keyte & Parrott (1992) reported a broadside of the text from 1795 in the holdings of the Newberry Library in Chicago; this could not be confirmed by the present editor.

Josiah Miller, “Frederick Oakeley, M.A.,” Singers and Songs of the Church (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1869), p. 696: Archive.org

Erik Routley, “O come, all ye faithful,” The English Carol (1958), p. 150.

Related Resources:

Vincent Novello, “The Portuguese Hymn,” The Congregational and Choristers’ Psalm and Hymn Book (London: Dufour, 1843), pp. 14–15: Google Books

William T. Brooke & John Julian, “Adeste fideles, laeti triumphantes,” A Dictionary of Hymnology (London: J. Murray, 1892), pp. 20–22: HathiTrust

James Love & William Cowan, “Adeste fideles,” The Music of Church Hymnary (Edinburgh: H. Frowde, 1901), pp. 5–8: Archive.org

G.E.P. Arkwright, “Notes and Queries,” The Musical Antiquary, vol. 1 (April 1910), pp. 188–189: HathiTrust

W.H. Grattan Flood, “Notes on the history of ‘Adeste Fideles,’” The Musical Times, vol. 56, no. 868 (June 1915), pp. 360–361: JSTOR

James T. Lightwood, “Adeste Fideles,” The Music of the Methodist Hymn Book (London: Epworth Press, 1935), pp. 97–100.

Dom John Stephan, The Adeste Fideles: A Study on Its Origin and Development (South Devon: Buckfast Abbey, 1947).

Albert Edward Bailey, “Adeste fideles,” The Gospel in Hymns (NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1950), pp. 278–279.

Erik Routley, “O come, all ye faithful,” The English Carol (London: Herbert Jenkins, 1958), pp. 146–151.

Maurice Frost, “O come, all ye faithful,” Historical Companion to Hymns Ancient & Modern (London: Williams Clowes & Sons, 1961), pp. 446–447.

Richard Watson & Kenneth Trickett, “O come, all ye faithful,” Companion to Hymns & Psalms (Peterborough: Methodist Publishing, 1988), pp. 97–98.

Fred L. Precht, “Oh come, all ye faithful,” Lutheran Worship Hymnal Companion (St. Louis: Concordia, 1992), pp. 50–52.

Hugh Keyte & Andrew Parrott, “Adeste Fideles,” New Oxford Book of Carols (Oxford: University Press, 1992), pp. 238–243.

Carlton R. Young, “O come, all ye faithful,” Companion to the United Methodist Hymnal (Nashville: Abindgon, 1993), pp. 502–503.

Nicholas Temperley, “O come, all ye faithful,” The Hymnal 1982 Companion, vol. 3A (NY: Church Hymnal Corp., 1994), pp. 159–162.

Bennett Zon, “The origin of Adeste Fideles,” Early Music, vol. 24, no. 2 (May 1996), pp. 279–288: JSTOR

Bennett Zon, “The Works of John Francis Wade,” The English Plainchant Revival (Oxford: University Press, 1999), pp. 104–140.

J.R. Watson, “O come, all ye faithful,” An Annotated Anthology of Hymns (Oxford: University Press, 2002), pp. 279–280.

Edward Darling & Donald Davison, “O come, all ye faithful,” Companion to Church Hymnal (Dublin: Columba, 2005), pp. 262–264.

Erik Routley, “O come, all ye faithful,” English Speaking Hymnal Guide, ed. Peter Cutts (Chicago: GIA, 2005), pp. 125–126.

Robert Cottrill, “O come, all ye faithful,” Wordwise Hymns (14 May 2012): https://wordwisehymns.com/2012/05/14/o-come-all-ye-faithful/

Carl P. Daw Jr., “O come, all ye faithful,” Glory to God: A Companion (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2016), pp. 137–139.

Marion Lars Hendrickson & Joseph Herl, “O come, all ye faithful,” Lutheran Service Book Companion to the Hymns, vol. 1 (St. Louis: Concordia, 2019), pp. 128–135.

Related Links:

University of Glasgow, University Collections, GB 247 MS Euing R.d.90 (superscript 2): http://collections.gla.ac.uk/#/details/ecatalogue/261158

Hymn Tune Index: https://hymntune.library.uiuc.edu/default.asp

“Hither, ye faithful,” Hymnary.org: https://hymnary.org/text/hither_ye_faithful_haste_with_songs_of_t

“O come, all ye faithful,” Hymnary.org: https://hymnary.org/text/o_come_all_ye_faithful_joyful_and_triump

Douglas D. Anderson & Richard Jordan, “Adeste fideles,” Hymns and Carols of Christmas: https://www.hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com/Hymns_and_Carols/NonEnglish/adeste_fideles.htm

Alan Luff, “Adeste fideles,” Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology: https://hymnology.hymnsam.co.uk/a/adeste,-fideles