Brightest and best of the sons of the morning

including

Hail the blest morn! when the Great Mediator

with

WANDERING WILLIE

STAR IN THE EAST

MORNING STAR

EPIPHANY

LIEBSTER IMMANUEL

I. Text: Origins

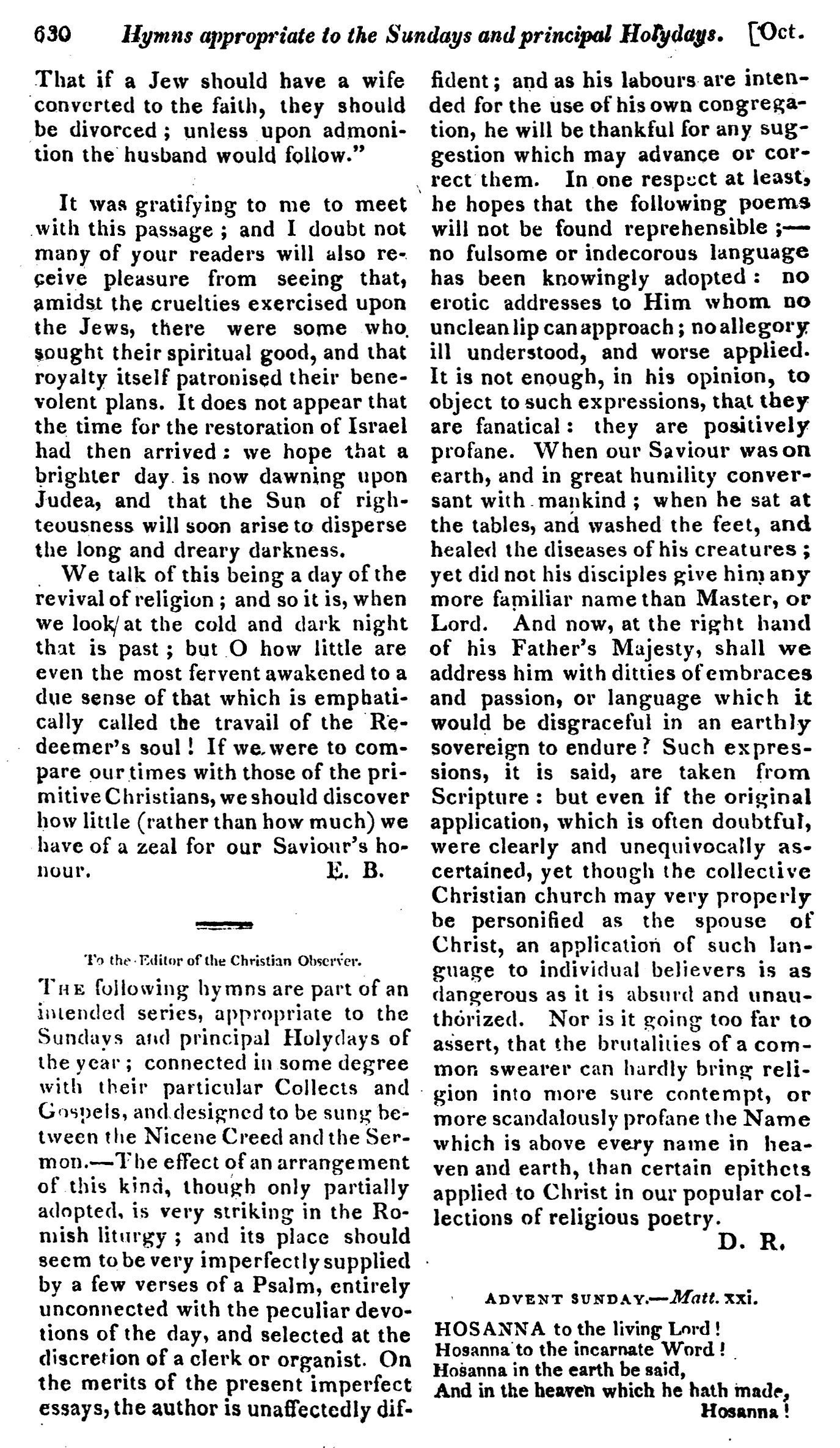

For fifteen years, Reginald Heber (1783–1826) had endeavored to develop a hymnal designed to offer hymns for every Sunday of the liturgical church year, the first of its kind in the Church of England. The earliest of these liturgical hymns were printed in The Christian Observer, October and November 1811, including “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning” (Fig. 1). The writer, here named only “D.R.,” stated his purpose:

The following hymns are part of an intended series, appropriate to the Sundays and principle Holydays of the year, connected in some degree with their particular collects and gospels, and designed to be sung between the Nicene Creed and the sermon.

In this case, “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning” was named as a hymn for Epiphany, given in five stanzas of four lines in the November 1811 issue.

Fig. 1. The Christian Observer, vol. 10, nos. 10–11 (Oct.–Nov., 1811).

Nine years later, 5 December 1820, still in want of a complete volume, Reginald Heber wrote to his friend Henry Hart Milman, asking for submissions, and he sent Milman a draft of the project for his review. Included in Heber’s manuscript draft was his hymn “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” this time appointed for Christmas Day (Fig. 2a). Notice the slight change in 2.2 from “Low lies his bed” to “Low lies his head,” and 4.2, from “Vainly with gold” to “Vainly with gifts.”

Fig. 2a. British Library, MS Add 25704, book 1, fols. 3v–4r.

On another page of the manuscript, the hymn was referenced as a possibility for Epiphany (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2b. British Library, MS Add 25704, book 1, fol. 6v.

Heber continued to work on the project and received submissions from Milman, but he died before his project could be published. In the meantime, this hymn had been printed in a few other collections, including The Evangelical Magazine (Aug. 1825) and James Montgomery’s Christian Psalmist (1825). Heber’s widow Amelia prepared his collection for print, Hymns Written and Adapted to the Weekly Church Service of the Year (London: John Murray, 1827 | Fig. 3). In this published version, “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning” had been moved from its Christmas Day slot back to an Epiphany slot. The only change from manuscript to print was the final conjunction of stanza 3, from “and” to “or.”

Fig. 3. Hymns Written and Adapted to the Weekly Church Service of the Year (London: John Murray, 1827).

II. Text: Analysis (Interpretation)

At its core, the hymn is a meditation on the arrival of the magi in Matthew 2. The opening line is an allusion to the personification of stars in Job 38:7 (“Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth . . . when the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?”). Regarding the second line, “Dawn on our darkness,” J.R. Watson believed this could be an allusion to the Book of Common Prayer, especially the Collect for Advent (“give us grace that we may cast away the works of darkness, and put upon us the armour of light”) or the Third Collect at Evening Prayer (“Lighten our darkness, we beseech thee, O Lord”).[1]

The second stanza is a step backward in time to the child’s birth in Luke 2, featuring the angels and “beasts of the stall,” which, if intended to be part of the narrative for Epiphany, is somewhat out of place, but still part of the overall arc of Christ’s infancy.

The third stanza names an array of gifts. The phrase “odours of Edom” carries some associations, Edom being the land of the descendants of Esau, described in Genesis 36 as “the hill country of Seir,” whose people were frequently treated in the Old Testament as the condemned enemies of Israel (“the people with whom the Lord is angry forever,” Mal. 1:4). It is known in biblical literature for exporting salt and balsam, which was used in perfumes and incense. Job 28 describes the mining of gold and minerals. In this stanza, the viewpoint shifts to that of the reader or worshiper, as if we were standing with the magi (Albert Edward Bailey: “the worshiping kings become ourselves”[2]).

The fourth stanza continues the view of application, explaining the futility of offering gifts such as these to gain the Savior’s favor. What the Messiah really wants is adoration, he who listens to the the prayers of the poor. These last two lines echo sentiments found in passages such as Psalm 51.16–17:

For you will not delight in sacrifice, or I would give it;

you will not be pleased with a burnt offering.

The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit;

a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise (ESV).

Bailey noted, “Having thus conjured up in our imagination the costliness of such an offering, we discover that in God’s sight these gifts are far less dear to him than is the love of our hearts.”[3] Other applicable passages in this stanza include Psalm 34:6,18, Matthew 5:1–12, and Luke 21:1–4.

British hymn writer Timothy Dudley-Smith was intrigued with Heber’s poetic use of word sounds:

Again, in Bishop Heber’s epiphany hymn, . . . the sense of rhythm and movement owes much to the feminine rhymes and the alliterations: Brightest/best, dawn/darkness, cold/cradle, dew/drops, low/lies, angels/adore, Maker/Monarch—all from the first two verses. But assonance comes into its own in verse 3. . . . This provides an alternation between the short and the long “o” in each of the lines: short–long in line 1, long–short–short in line 2, short–short–long in line 3, short–short–long–short in line 4. Three of these “o” sounds at the start of words add the more obvious alliteration to the almost unnoticed assonance. I am not suggesting that this pattern was a deliberate construct of the writer, but in the choices the mind makes when clothing thought with language these things somehow emerge almost of themselves.[3]

III. Text: Reception and Alteration

The hymn has had an interesting history of being both loved and criticized. On the positive side, Albert Edward Bailey said it “adorns and interprets the straight-forward gospel story with beautiful imagery from nature,”[4] Pastor Robert Cottrill said, “It offers a touching portrayal of the manger scene”[5], Fred L. Precht said, “it fully merits its general popularity,”[6] and Percy Dearmer called it “One of the best of Heber’s pioneer hymns.”[7]

John Julian was one of the earliest to note its detractors, explaining, “Few hymns of merit have troubled compilers more than this. Some have held that its use involved the worshiping of a star, whilst others have been offended with its metre as being too suggestive of a solemn dance.”[8] Percy Dearmer blasted the criticism with less restraint:

Dunderheaded critics held this back from use on the ground that it involved the worshiping of a star. . . . Others objected that the metre (so fashionable in the age of Tom Moore) was Terpsichorean, being averse to praising God with cymbals and dances. . . . Hymns Ancient & Modern, by rejecting it in 1861, caused large sections of Victorian church-goers to be ignorant of it.[9]

Some hymnal compilers have opted to change the first line of the text to read “Brightest and best of the stars of the morning,” owing to concern about the sons being confused either for Satan or angels. This alteration, beginning with the Lutheran Book of Worship (1978), was explained by Fred L. Precht:

Since Heber’s “sons of the morning” in the opening line appeared, to some at least, to refer to Isaiah 14:12, where in the Authorized Version Lucifer is so described, or where, according to Job 38:7, “morning stars” and “sons of God” are perhaps angels joining in the praise of God for his wonderful act of creation, the Inter-Lutheran Commission on Worship deemed it advisable to avoid such possible misinterpretations by changing “sons of the morning” to “stars of the morning,” thus referring perhaps less mistakably to the “star of the east,” the star which the Magi saw, as indicated in Matthew 2:1–2.[10]

The Lutheran Book of Worship also instituted the change from “Odours” to “Fragrance” at 3.2. Some hymnals in the United Kingdom, following the example of Hymns for Today’s Church (1987), have opted for the line “Brightest and best of the suns of the morning.”

In his literary analysis from 1997, J.R. Watson was a critic of the way Heber shifted his text from narrative painting in the first two stanzas to “moralizing” in the next two, lamenting how “Heber begins to preach,” offering a predictable response to the question posed in stanza 3 (“shall we yield him . . . gold from the mine?”):

The answer, of course, is no: dearer to God are the prayers of the poor. This is unexceptionable, but also commonplace, and a dull conclusion to the radiant epiphanic vision of the first two verses. From this dreary homily, Heber has to rescue the hymn by going back to the first verse . . .[11]

In his later anthology, Watson still bemoaned the “rather obvious sermon” but retreated a bit from his approach to the ending, saying, “The repetition of the first verse at the end is like the revisiting of a picture in an art gallery, so that we are left with the lovely vision of the infant Jesus.”[12] In response to Watson’s criticism of the transition from stanza 2 to 3, Lutheran scholar David Rogner offered, “To the extent that hymns should have a didactic function, however, Heber accomplishes it in the next two stanzas.”[13]

Finally, Albert Edward Bailey took issue with the disparity between Heber’s reported financial standing and his lines about the poor, in an unguarded attack on Heber’s personal character and the Church of England:

Does God love to have poor people beg him for the things they desperately need, as Heber was glad to hand out a dole to them from his palatial vicarage? But we must not be hard on the good poet. He and his Church had not yet begun to realize that God hates poverty as much as he hates pride.[14]

IV. Tunes

1. WANDERING WILLIE

In a biography of Heber published in 1895, the author described a manuscript hymnal made by Heber for use at his church at Hodnet, which included suitable tunes.[15] For this hymnal, the text had been paired with a Scottish folk tune called WANDERING WILLIE, which is associated with a text by Scottish poet Robert Burns (1759–1796), beginning, “Here awa,’ there awa,’ here awa,’ Willie,” or more commonly, “Here awa,’ there awa,’ wandering Willie.” The melody was printed in Burns’ lifetime in The Scots Musical Museum, vol. 1 (Edinburgh: James Johnson, 1787 | Fig. 4). The current location of Heber’s music manuscript is unknown.

Fig. 4. The Scots Musical Museum, vol. 1 (Edinburgh: James Johnson, 1787).

For other editions of this tune, see Songs of Robert Burns with Music (1859 | Archive.org) or The Songs of Robert Burns (1903 | Archive.org). In spite of Heber’s reported intent, and the frequent mention of this tune in hymnal commentaries, this tune does not appear to have ever been adopted as a hymn tune, much less printed with Heber’s text.

2. STAR IN THE EAST

Another of the earliest tune settings is a folk tune, this one born out of American shape-note tunebooks. The tune is attached to a tradition in which Heber’s hymn was given a new opening stanza, “Hail the blest morn! When the Great Mediator,” and the first stanza was made into a refrain. The earliest known example of this was printed in Brick Church Hymns (1823 | Fig. 5), made for the Brick Presbyterian Church in New York City.

Fig. 5. Brick Church Hymns (NY: Brick Church, 1823).

The melody most closely associated with this version of Heber’s hymn is STAR IN THE EAST, the earliest known printing of which was in Japheth Coombs Washburn’s The Temple Harmony, 6th ed. (1826 | Fig. 6) in three parts, using round notes. This tune uses a natural minor scale (Aeolian mode), except in Washburn’s version the final two instances of 7 are raised as leading tones. In this style of part writing, harmonic thirds are often omitted, giving the performance a stark, haunting sound.

Fig. 6. The Temple Harmony, 6th ed. (Hallowell, ME: Glazier & Co., 1826). Melody in the middle part.

In 1994, Marion Hatchett described how the tune had spread quickly across the United States and was widely adopted into other collections. The most influential of these latter printings was in the popular shape-note tunebook Southern Harmony (Spartanburg, S.C.: William Walker, 1835 | Fig. 7), edited by William Walker, where it was given in three parts. Like Washburn’s arrangement, Walker’s left many of the fifths open, not concerned with filling triads. Walker’s version, however, is devoid of raised sevenths. The attribution “Baptist Harmony, p. 35” is in reference to the appearance of this text in Staunton Burdett’s Baptist Harmony (1834).

Fig. 7. Southern Harmony (Spartanburg, S.C.: William Walker, 1835). Melody in the middle part.

When William Walker printed this song in his Christian Harmony (Philadelphia: William Walker, 1867 | Fig. 8), he added a fourth harmony part. In this case, the additional voice was not intended to fill the empty thirds, so the arrangement still retains much of its hollow sound.

Fig. 8. Christian Harmony (Philadelphia: William Walker, 1867). Melody in the tenor part.

3. MORNING STAR

The other most common tune for Heber’s hymn in the United States has been MORNING STAR, said to have been composed in June 1892 by James P. Harding (1850–1911) as a choir anthem for the Gifford Hall Mission in Islington, London, England. Harding served thirty-five years as organist and choirmaster of St. Andrew’s Church, Thornhill Square, Islington, London. His anthem was published by Novello, Ewer & Co. (Fig. 9). The British Library copy is stamped 12 Oct. 1892.

Fig. 9. “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning” (London: Novello, Ewer & Co., 1892).

This tune’s first appearance in a hymnal and its general overall success has been in the United States, starting with the Episcopal Church Hymnal (1894 | Fig. 10), in particular, the music edition prepared by Charles L. Hutchins. Catholic writer George William Rutler expressed, “MORNING STAR conspicuously fits the feel of the season and the text.”[16]

Fig. 10. Church Hymnal, ed. Charles Hutchins (Boston: Parish Choir, 1894).

4. EPIPHANY

In the United Kingdom, Heber’s text has often been printed with EPIPHANY HYMN, a tune by Joseph Francis Thrupp (1827–1867), vicar of Barrington, Cambridge, first printed in James Turle’s Psalms and Hymns for Public Worship (1863 | Fig. 11a) and in the Bristol Tune Book (1863 | Fig. 11b). In both cases, the tune was dated 1848 and intended for Heber’s text. The harmonizations were identical as well. The only difference between the two was the presence of a leaping seventh in the last phrase of the Bristol Tune Book. The leap is not typically used in other collections.

Fig. 11a. Psalms and Hymns for Public Worship (London: SPCK, 1863).

Fig. 11b. Bristol Tune Book (1863).

5. LIEBSTER IMMANUEL

Out of all the tunes given here for Heber’s text, this is the only one not originally written for it; it is also the most sophisticated. It comes from a German hymn, “Liebster Immanuel, Herzog der frommen,” text attributed to Ahasverus Fritsch (1629–1701), first printed in Himmels-Lust und Welt-Unlust (Jena: Johann Nisien, 1679 | Fig. 12, pending).

In German, the tune endured a great number of variations, many of which were documented by Johannes Zahn (1890). The version of the tune as it is known to English worshipers, featuring a static opening triplet, came to greater prominence via its inclusion in Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cantata BWV 123 (1725 | Fig. 13). Bach’s harmonization is sometimes repeated in English hymnals.

Fig. 13. Cantata 123, Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe, Bd. 26 (Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1878). Melody in the soprano.

The adoption of the German tune into English (with one exception in 1885) and its association with Heber’s text came through The English Hymnal (1906 | Fig. 14), using the harmonization by Bach. The “major tune” referenced here is Thrupp’s tune EPIPHANY.

Fig. 14. The English Hymnal (Oxford: University Press, 1906).

Regarding this tune, Archibald Jacob remarked, “Both the original and the later version are sterling tunes; the motive of some of the alterations, however, is not apparent, especially in the 1st and the 9th and 10th bars.”[17]

For an English translation of the German text, “Dearest Immanuel, Prince of the lowly” by M. Woolsey Stryker, using Bach’s harmonization, see Christian Chorals (1885 | Hymnary.org).

by CHRIS FENNER

for Hymnology Archive

10 December 2020

rev. 7 January 2022

Footnotes:

J.R. Watson, Companion to Hymns and Psalms (1988), p. 104; also J.R. Watson, Annotated Anthology (2002), p. 240.

Albert Edward Bailey, The Gospel in Hymns (1950), p. 146.

Timothy Dudley-Smith, A Functional Art: Reflections of a Hymn Writer (Oxford: University Press, 2017), pp. 97–98.

Albert Edward Bailey, The Gospel in Hymns (1950), p. 146.

Robert Cottrill, Wordwise Hymns (11 Aug. 2014).

Fred L. Precht, Lutheran Worship Hymnal Companion (1992), p. 95.

Percy Dearmer, Songs of Praise Discussed (1933), p. 59.

John Julian, A Dictionary of Hymnology (1892), p. 182.

Percy Dearmer, Songs of Praise Discussed (1933), p. 59.

Fred L. Precht, Lutheran Worship Hymnal Companion (1992), p. 95; see also The Hymnal 1940 Companion (1956), p. 38.

J.R. Watson, The English Hymn (1997), p. 323.

J.R. Watson, An Annotated Anthology of Hymns (2002), p. 240.

David Rogner, Lutheran Service Book Companion to the Hymns, vol. 1 (2019), p. 195.

Albert Edward Bailey, The Gospel in Hymns (1950), pp. 146–147.

George Smith, Bishop Heber, Poet and Chief Missionary to the East (London: J. Murray, 1895), p. 92: Archive.org

George William Rutler, “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” The Stories of Hymns (2016), p. 211.

Archibald Jacob, “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” Songs of Praise Discussed (1933), p. 59.

Related Resources:

Johannes Zahn, Die Melodien der deutschen evangelischen Kirchenlieder, vol.3 (Gütersloh: C. Bertelsmann, 1890), no. 4932: Archive.org

John Julian, “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” A Dictionary of Hymnology (London: J. Murray, 1892), p. 182: HathiTrust

Percy Dearmer & Archibald Jacob, “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” Songs of Praise Discussed (Oxford: University Press, 1933), p. 59.

Albert Edward Bailey, “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” The Gospel in Hymns (NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1950), p. 146.

“Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” The Hymnal 1940 Companion, 3rd rev. ed. (NY: Church Pension Fund, 1956), p. 38.

J.R. Watson & Kenneth Trickett, “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” Companion to Hymns and Psalms (Peterborough: Methodist Publishing, 1988), pp. 104–105.

Fred L. Precht, “Brightest and best of the stars of the morning,” Lutheran Worship Hymnal Companion (St. Louis: Concordia, 1992), pp. 94–95.

Hugh Keyte & Andrew Parrott, “Hail the blest morn!” New Oxford Book of Carols (Oxford: University Press, 1992), pp. 294–297.

Carol A. Doran & Marion Hatchett, “Brightest and best of the stars of the morning,” The Hymnal 1982 Companion, vol. 3A (NY: Church Hymnal Corp., 1994), pp. 243–248.

J.R. Watson, “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” An Annotated Anthology of Hymns (Oxford: University Press, 2002), pp. 239–240.

David W. Music, “STAR IN THE EAST,” A Selection of Shape-Note Folk Hymns, Recent Researches in American Music, vol. 52 (Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, 2005), p. lii.

Edward Darling & Donald Davison, “Brightest and best of the suns of the morning,” Companion to Church Hymnal (Dublin: Columba, 2005), pp. 287–288.

Robert Cottrill, “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” Wordwise Hymns (11 Aug. 2014): https://wordwisehymns.com/2014/08/11/brightest-and-best-of-the-sons-of-the-morning/

George William Rutler, “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” The Stories of Hymns (Irondale, AL: EWTN, 2016), pp. 210–212.

David Rogner & Joseph Herl, “Brightest and best of the stars of the morning,” Lutheran Service Book Companion to the Hymns, vol. 1 (St. Louis: Concordia, 2019), pp. 195–197.

Leland Ryken, “Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” 40 Favorite Hymns for the Christian Year (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2020), pp. 150–153.

“Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,” Hymnary.org:

https://hymnary.org/text/brightest_and_best_of_the_sons_of_the_mo

“Hail the blest morn! See the Great Mediator,” Hymnary.org:

https://hymnary.org/text/hail_the_blest_morn_see_the_great_mediat