Hark how all the welkin rings

revised as

Hark! the herald angels sing

with

SALISBURY

MENDELSSOHN

WE’LL WALK IN THE LIGHT

I. Text: Origins

The Wesleys had an enduring friendship and connection with George Whitefield (1714–1770), beginning with their Oxford “Holy Club,” followed by separate missionary journeys to America, and a call to open-air field preaching in England. During the earlier years of that association, the Wesleys published some of their most enduring poetry, especially in the first edition of Hymns and Sacred Poems (1739). In this collection, Charles Wesley had penned a Christmas hymn with a curious text: “Hark how all the Welkin rings / Glory to the King of Kings” (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Hymns and Sacred Poems (1739).

Fig. 2. William Somerville, The Chase (1735).

A modern reader might see the words “welkin rings” and immediately gravitate to something from J.R.R. Tolkien, but “welkin” means “sky” or “heavens” — it was a common term in English poetry in that era. Wesley might have been alluding directly to a poem by William Somerville about fox hunting, called “The Chase” (1735 | Fig. 2):

The welkin rings, Men, Dogs, Hills, Rock, and Woods

In the full consort join.

Hymn scholar J.R. Watson explained:

To have altered Somerville’s lines would have been in keeping with Wesley’s habit of appropriating images from other poems and using them to proclaim the gospel. Here the cries of the huntsmen and hounds become the sounds of the multitude of the heavenly host, praising God, and saying, “Glory to God in the highest.”[1]

In the second edition of Hymns and Sacred Poems (1739), Wesley made one minor change to the first line of the fifth stanza, which became “Hail the heaven-born Prince of Peace.”

II. Text: Development

As clever as Wesley’s allusion to welkin rings might have been, it failed to resonate with some worshipers, including his friend and colleague George Whitefield. In 1753, the same year Whitefield began construction on the Tabernacle church, he compiled his own hymnal, A Collection of Hymns for Social Worship. It included 21 hymns from the Wesleys, including the Christmas hymn, but with a significant alteration:

Hark! the Herald Angels sing

Glory to the new-born King! (Fig. 3)

Whitefield made other alterations as well, including the second stanza, lines 3–4, the fifth stanza, “Light and life around he brings,” the seventh stanza, “Fix in us thy heav’nly home,” the omission of stanzas eight and ten, and a change in the last line of nine, “Work it in us by thy love.”

Fig. 3. George Whitefield, A Collection of Hymns for Social Worship (1753).

In 1760, Martin Madan borrowed Whitefield’s opening lines but kept the rest of Wesley’s wording, except in the second stanza, where he introduced the lines “With th’ angelic host proclaim, / Christ is born in Bethlehem!” This version appeared in Madan’s A Collection of Psalms and Hymns (1760 | Fig. 4).

John Wesley chose not to include this hymn in the career-spanning Collection of Hymns for the Use of the People Called Methodists (1780). A few years later, after being entreated to produce a smaller, more affordable collection, he published A Pocket Hymn Book, first in 1785, then greatly revised in 1787. The Christmas hymn was added to the revised edition, but restructured into four stanzas of eight lines, incorporating Whitefield’s opening lines and Madan’s new text, effectively making Madan’s version the official Wesleyan text (Fig. 5).

Starting in 1782, editions of the New Version of the Psalms of David printed this hymn with the first two lines repeated as a refrain after every stanza (“Hark the herald angels sing / Glory to the newborn King” | Fig. 6). Note also the reduction of the text to three stanzas of eight lines, a form still utilized in modern hymnals.

The common alteration “Pleased as man with men to dwell, / Jesus our Emmanuel” appeared as early as 1810 in John Kempthorne’s Select Portions of Psalms. This version was popularized especially through Hymns Ancient & Modern (1861 | Fig. 7). In 1904, the editors of Hymns Ancient & Modern infamously changed the text back to “welkin rings”; they were so soundly ridiculed about this and other issues, in the next edition (1906), a re-release of the 1889 edition, they returned to “herald angels.”[2]

Fig. 4. Martin Madan, A Collection of Psalms and Hymns (1760).

Fig. 5. John Wesley, A Pocket Hymn Book, 2nd ed. (1787).

Fig. 6. New Version of the Psalms of David (1782).

Fig. 7. Hymns Ancient & Modern (1861).

III. Tunes

1. SALISBURY (EASTER HYMN)

“Hark, how all the welkin rings” was first published with music in A Collection of Hymns and Sacred Poems (Dublin: S. Powell, 1749 | Fig. 8), set to SALISBURY (better known as the tune for “Christ the Lord is risen today”). The editor of this collection was not credited, but it was quite possibly John Frederick Lampe (1702/3–1751), who had written a set of tunes for the Wesleys, Hymns on the Great Festivals (1746), and had moved to Dublin in Sept. 1748 to produce some works for a theatre there.

Fig. 8. A Collection of Hymns and Sacred Poems (Dublin: S. Powell, 1749).

This musical pairing is curious, but it works. The joyful, triumphant tune fits the angelic declaration at Christ’s birth in much the same way as it fits a text for Christ’s resurrection. The history of this tune is treated in greater detail in the article on the resurrection hymn, but here it should suffice to note how the Wesleys had enjoyed the use of this tune for many years, beginning with the Collection of Tunes, Set to Music, As They are Commonly Sung at the Foundery (1742), through their last tune book, Sacred Harmony (1780). “Hark! the herald angels sing” was marked SALISBURY in the revised Pocket Hymn Book (1787 | Fig. 5).

2. MENDELSSOHN

The most widely adopted tune for this text is MENDELSSOHN, by Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809–1847), from the second part of his Festgesang, WoO 9 (1840; Breitkopf & Härtel edition, Series 15, No. 120: Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Festgesang, WoO 9 (1840; Breitkopf & Härtel edition, Series 15, No. 120).

Mendelssohn’s music was adapted by William Cummings (1831–1915) as a hymn tune for his congregation at Waltham Abbey, first published as sheet music by J.J. Ewer & Co. in 1856 (Fig. 10), set to Wesley’s Christmas hymn.

Fig. 10. William H. Cummings, “Hark the herald angels sing” (London: J.J. Ewer & Co., 1856).

MENDELSSOHN was then included in the Congregational Hymn and Tune Book (Bristol, 1857 | Fig. 11) in a four-part congregational setting. This pairing of text and tune was further popularized via Hymns Ancient & Modern (1861).

Fig. 11. Congregational Hymn and Tune Book (1857).

Somewhat ironically, Mendelssohn did not believe this tune would work with a sacred text. In a letter of 30 April 1843, reprinted many years later in The Musical Times (Dec. 1897), p. 810, he wrote to his English publisher, E. Buxton, regarding a translation of his Festgesang which had been prepared by William Bartholomew:

I think there ought to be other words to No. 2, the “Lied.” If the right ones were hit at, I am sure that piece will be liked very much by the singers and the hearers, but it will never do to sacred words. There must be a national and merry subject found out, something to which the soldierlike and buxom motion of the piece has some relation, and the words must express something gay and popular, as the music tries to do it.

Little did Mendelssohn know that his tune would become very popular, set to a merry subject indeed.

3. WE’LL WALK IN THE LIGHT

The gospel tune and refrain known as “Jesus, the Light of the World” or WE’LL WALK IN THE LIGHT has its roots in a song with lyrics by Fanny Crosby (1820–1915) and music by W.H. Doane (1832–1915), beginning “Shining in darkness by faith we behold,” from Good As Gold (1880 | Fig. 12). In this song, notice the 6/8 time, the inner (or interlinear) refrain, “Jesus, the light of the world,” two fermatas in the refrain, and the text of the full refrain.

Fig. 12. Good As Gold (NY: Biglow & Main, 1880).

The song by Crosby and Doane was republished in Hymn Service No. 3 (1881) and in The Bright Array (1889), then not again in either of their lifetimes. In 1890, a new version emerged as arranged by Chicago composer-publisher George D. Elderkin (1845–1928) for The Finest of the Wheat (1890 | Fig. 13). Here, the song was an amalgamation of Wesley’s text, “Hark! the herald angels sing,” interspersed with the inner refrain “Jesus, the light of the world,” plus an alteration of Fanny’s Crosby’s textual refrain, all set to a different tune than what Doane had written, but still in 6/8 and still with an introductory fermata at the beginning of the refrain. This version of the song has survived largely unchanged to the present day.

Fig. 13: The Finest of the Wheat (Chicago: R.R. McCabe & Co., 1890).

Hymn scholar Carl Daw has raised the question of how much Elderkin’s version was compositionally his and how much potentially came from camp-meeting influences. In the 1890 printing, Elderkin only claimed to be the arranger of text and tune. Certainly, the text was not his, nor was the overall musical concept. But had something like this circulated orally before Elderkin committed it to print? Wandering refrains were part of the culture, as seen in other famous examples like “At the cross” or “Oh, how I love Jesus.” Aside from the Crosby/Doane song, no other examples of this refrain have been identified between 1880 and 1890. But after 1890, there are several.

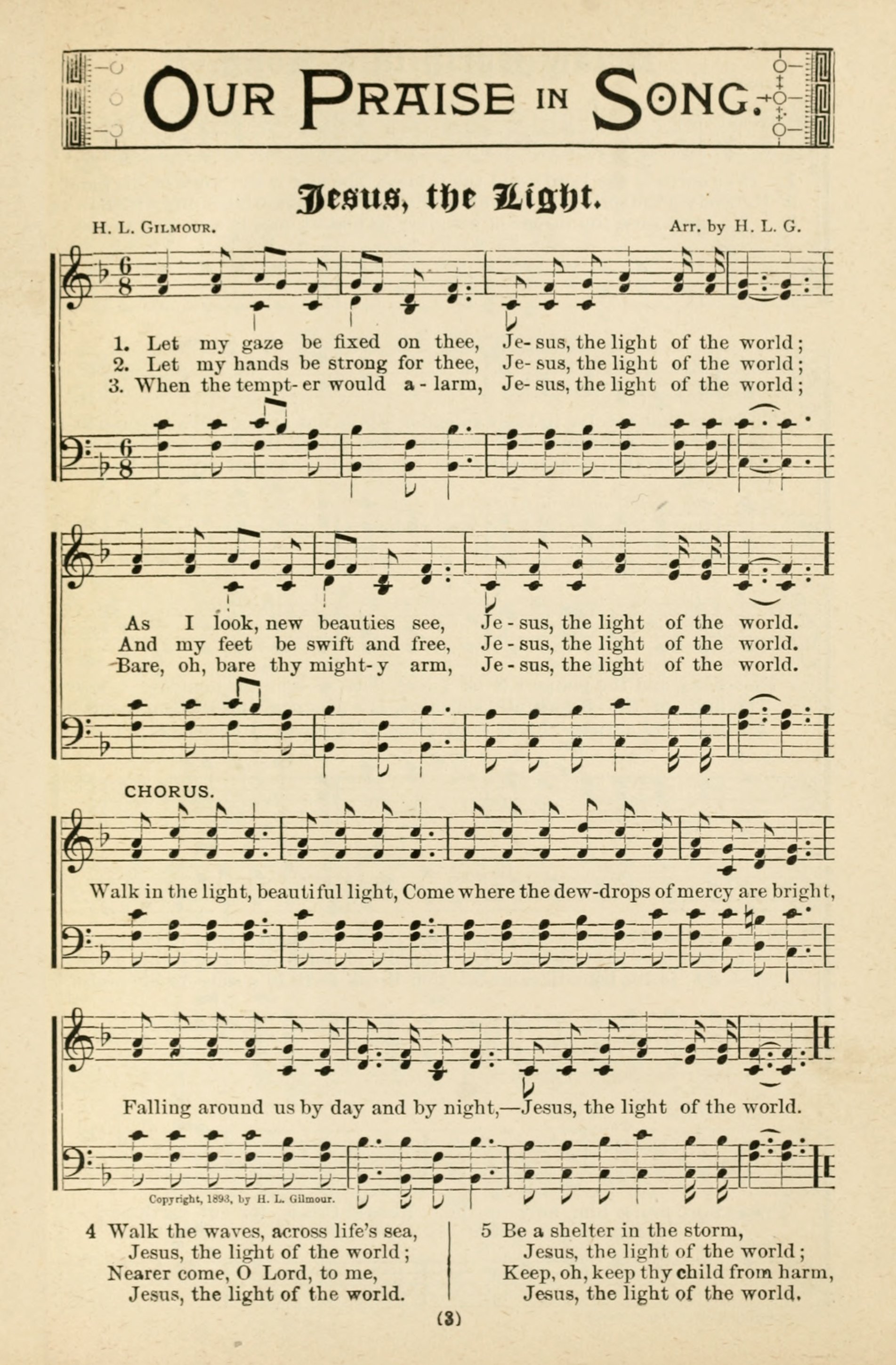

In 1891, Peter Bilhorn offered his own version of this text-plus-refrain in Crowning Glory No. 2 (Fig. 14). Bilhorn was also based in Chicago, so this example could be explained easily as a case of local imitation, especially seeing how Bilhorn used Wesley’s royalty-free text while avoiding the Crosby/Elderkin refrain. Nevertheless, the possible case for a wandering camp-meeting refrain spills out across eight other examples identified by Daw from 1893 to 1910, the first of which is shown here at Fig. 15, “Let my gaze be fixed on thee” in Our Praise in Song (1893). Henry L. Gilmour was based in New Jersey and was known for directing music at camp meetings.

Fig. 14. Crowning Glory No. 2 (Chicago:

Fig. 15. Our Praise in Song (Philadelphia: John J. Hood, 1893).

The ultimate question is whether Gilmour’s example and others like it are borrowings from Elderkin, or mutual borrowings from an earlier, unwritten tradition. Seeing how Gilmour did not copy from Elderkin word-for-word or note-for-note, the temptation is to say Gilmour learned the tune and refrain informally, and perhaps Elderkin had done the same. Hymnal editors would not be wrong for crediting Elderkin with the tune, because he was the first person to put it in print, but the text of the refrain is clearly not his, it is by Fanny Crosby.

Many hymnals in the 21st century use an arrangement by Evelyn Simpson-Currenton, made for the African American Heritage Hymnal (2001).

by CHRIS FENNER

for Hymnology Archive

21 June 2018

rev. 8 December 2022

Footnotes:

J.R. Watson, “Welkins,” Hymn Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Bulletin (July 2000), p. 80.

Timothy Dudley-Smith, “Hark! the herald angels sing,” Canturbury Dictionary of Hymnology: http://www.hymnology.co.uk/h/hark!-the-herald-angels-sing

Related Resources:

William Somerville, The Chase: A Poem (Dublin: R. Reilly, 1735 | PDF).

“Hark! the herald angels sing,” The Musical Times, vol. 38, no. 658 (Dec. 1897), p. 810: PDF

John Julian, “Hark how all the welkin rings,” A Dictionary of Hymnology (London, 1892), pp. 487–488: Google Books

Fred L. Precht, “Hark! the herald angels sing,” Lutheran Worship Hymnal Companion (St. Louis: Concordia, 1992), pp. 59–61.

Geoffrey Wainwright & Robin Leaver, “Hark! the herald angels sing,” The Hymnal 1982 Companion (NY: Church Hymnal Corp., 1994), no. 87.

Madeleine Forell Marshall, “Hark! the herald angels sing,” Common Hymnsense (Chicago: GIA, 1995), pp. 47–52.

John Lawson, “Hark, how all the welkin rings,” A Thousand Tongues: The Wesley Hymns as a Guide to Scriptural Teaching (London: Paternoster, 2007), p. 52: WorldCat | Amazon

Chris Fenner, “How George Whitefield reshaped a famous Christmas carol,” The Towers, SBTS, vol. 13, no. 4 (Nov. 2014), p. 20.

Carl P. Daw Jr., “Hark! the herald angels sing: Jesus the light of the world,” Glory to God: A Companion (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2016), pp. 130–131.

Leland Ryken, “Hark! the herald angels sing,” 40 Favorite Hymns for the Christian Year (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2020), pp. 132–135.

Gordon A. Knights, “Hymns Ancient & Modern,” Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology:

https://hymnology.hymnsam.co.uk/h/hymns-ancient-and-modern

“Hark! the herald angels sing,” Hymnary.org:

https://hymnary.org/text/hark_the_herald_angels_sing_glory_to