The Ninety and Nine

I. Text: Origins

The text of this hymn is by Elizabeth Clephane (1830–1869), who had a lifelong fondness for storytelling and literary pursuits, but whose limited hymnic output reached a broader audience only a year before she died, and in some cases, posthumously. In 1868, she had been invited by a friend of hers, the editor of The Children’s Hour, to submit material. In reply, she wrote her poem “The Lost Sheep,” beginning “There were ninety and nine that safely lay,” which is based on the parable in Matthew 18:10–14 and its parallel in Luke 15:1–7. It was probably written at her home in Melrose, Scotland. The original text was printed in five stanzas of six lines, without music, and signed “Bessie” (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The Children’s Hour (1868), pt. 2, p. 15.

After the text was published in The Children’s Hour, it was printed posthumously in The Family Treasury (1874), p. 595, under the heading “Breathings on the Border.” Her other most famous hymn, “Beneath the cross of Jesus,” had been printed in a similar manner in The Family Treasury (1872), pp. 398–399. “The Ninety and Nine” was repeated in a newspaper called The Christian Age (London), 13 May 1874, where it caught the attention of Ira Sankey (see below).

II. Tune

Musical evangelist and composer Ira Sankey (1840–1908) wrote a detailed account of how he found the text and how he came to compose a melody for it:

It was in the year 1874 that the poem “The Ninety and Nine” was discovered, set to music, and sent out upon its world-wide mission. Its discovery seemed as if by chance, but I cannot regard it otherwise than providential. Mr. Moody had just been conducting a series of meetings in Glasgow, and I had been assisting him in his work as director of the singing. We were at the railway station at Glasgow and about to take the train for Edinburgh, whither we were going upon an urgent invitation of ministers to hold three days of meetings there before going into the Highlands. We had held a three months’ series in Edinburgh just previous to our four months’ campaign in Glasgow. As we were about to board the train I bought a weekly newspaper for a penny. Being much fatigued by our incessant labors at Glasgow, and intending to begin work immediately upon our arrival at Edinburgh, we did not travel second or third class, as was our custom, but sought the seclusion and rest which a first-class railway carriage in Great Britain affords. In the hope of finding news from America, I began perusing my lately purchased newspaper. This hope, however, was doomed to disappointment, as the only thing in its columns to remind an American of home and native land was a sermon by Henry Ward Beecher.

I threw the paper down, but shortly before arriving in Edinburgh I picked it up again with a view to reading the advertisements. While thus engaged, my eyes fell upon a little piece of poetry in a corner of the paper. I carefully read it over, and at once made up my mind that this would make a great hymn for evangelistic work—if it had a tune. So impressed was I that I called Mr. Moody’s attention to it, and he asked me to read it to him. This I proceeded to do with all the vim and energy at my command. After I had finished I looked at my friend Moody to see what the effect had been, only to discover that he had not heard a word, so absorbed was he in a letter which he had received from Chicago. My chagrin can be better imagined than described. Notwithstanding this experience, I cut out the poem and placed it in my musical scrap-book—which, by the way, has been the seedplot from which sprang many of the Gospel songs that are now known throughout the world.

At the noon meeting on the second day, held at the Free Assembly Hall, the subject presented by Mr. Moody and other speakers was “The Good Shepherd.” When Mr. Moody had finished speaking, he called upon Dr. Bonar to say a few words. He spoke only a few minutes, but with great power, thrilling the immense audience by his fervid eloquence. At the conclusion of Dr. Bonar’s words Mr. Moody turned to me with the question, “Have you a solo appropriate for this subject, with which to close the service?” I had nothing suitable in mind, and was greatly troubled to know what to do. The Twenty-third Psalm occurred to me, but this had been sung several times in the meeting. I knew that every Scotchman in the audience would join me if I sang that, so I could not possibly render this favorite psalm as a solo. At this moment I seemed to hear a voice saying: “Sing the hymn you found on the train!” But I thought this impossible, as no music had ever been written for that hymn. Again the impression came strongly upon me that I must sing the beautiful and appropriate words I had found the day before, and placing the little newspaper slip on the organ in front of me, I lifted my heart in prayer, asking God to help me so to sing that the people might hear and understand. Laying my hands upon the organ I struck the key of A-flat, and began to sing.

Note by note the tune was given, which has not been changed from that day to this. As the singing ceased a great sigh seemed to go up from the meeting, and I knew that the song had reached the hearts of my Scotch audience. Mr. Moody was greatly moved. Leaving the pulpit, he came down to where I was seated. Leaning over the organ, he looked at the little newspaper slip from which the song had been sung, and with tears in his eyes said: “Sankey, where did you get that hymn? I never heard the like of it in my life.” I was also moved to tears and arose and replied: “Mr. Moody, that’s the hymn I read to you yesterday on the train, which you did not hear.” Then Mr. Moody raised his hand and pronounced the benediction, and the meeting closed. Thus “The Ninety and Nine” was born.[1]

After this experience, Sankey sent the text to his colleague P.P. Bliss in Chicago. Whether Sankey sent a sketch or description of his new tune is unclear, but Bliss wrote his own version and published it in his Gospel Songs (1874 | Fig. 2), which was released in late November or early December. Bliss’s tune has not endured.

Fig. 2. Gospel Songs: A Choice Collection of Hymns and Tunes (1874).

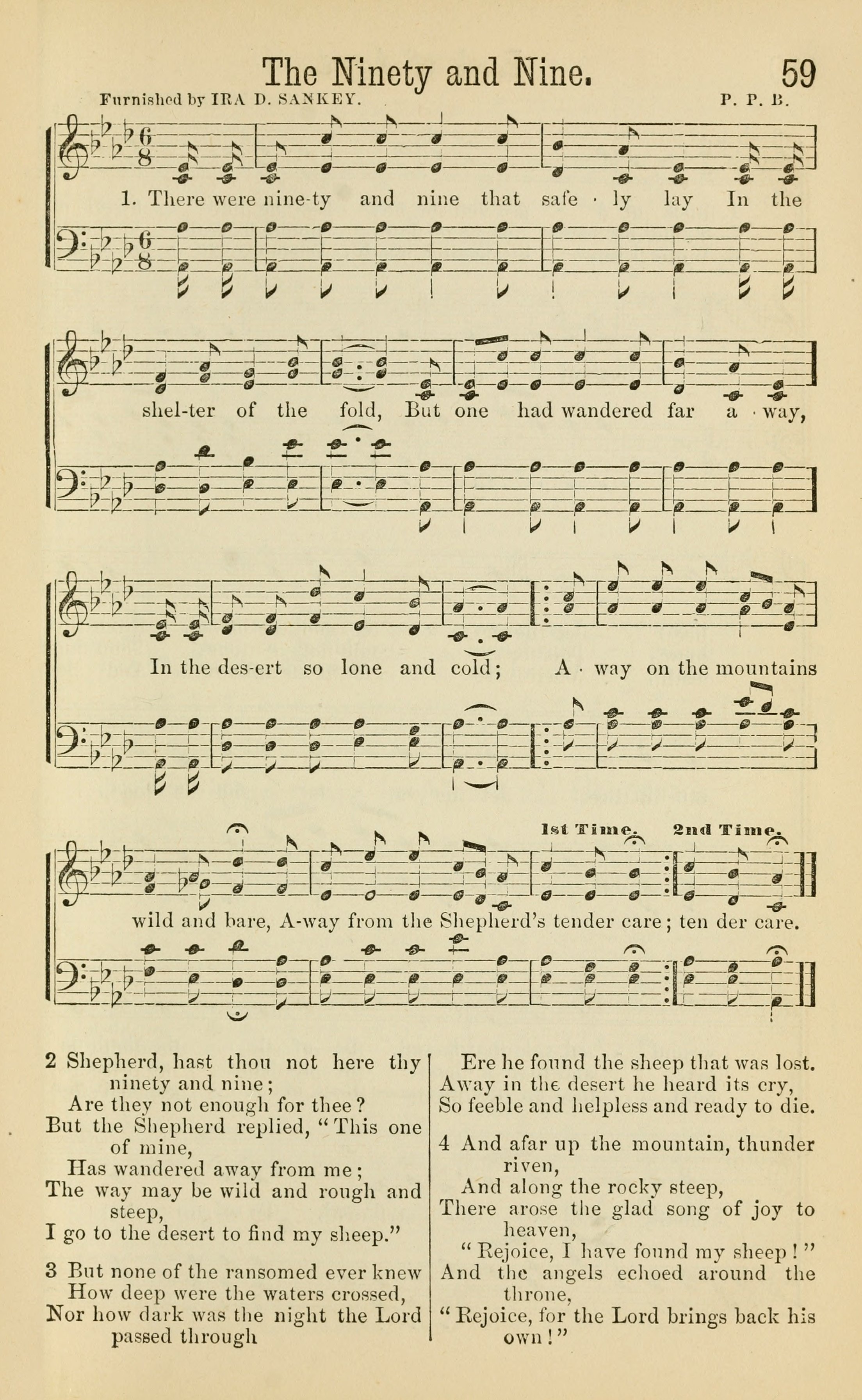

The providential nature of Sankey’s performance in Edinburgh had another twist: in the audience that night was one of Elizabeth Clephane’s sisters, who then wrote to Sankey and told him more about the writer of the words he had found. The following year, Sankey included the hymn in Gospel Hymns and Sacred Songs (1875 | Fig. 2), properly credited to Elizabeth Clephane. In this first publication of Sankey’s tune, the harmonization was relatively simple, using only three chords (I, IV, V), as might be expected from an improvised performance, but this is also in line with the genre as a whole.

Fig. 2. Gospel Hymns and Sacred Songs (NY: Biglow & Main, 1875).

The following year, when the hymn was included in Gospel Hymns No. 2 (1876), the harmonization was altered to include a brief excursion into F minor in the third phrase. This change was included in all subsequent editions. Mel Wilhoit, a scholar of Sankey’s life and work, believed it was probably Bliss who would have made that change, or possibly the publisher, Hubert P. Main (1839–1925).[2]

Several years later, in 1898, Ira Sankey had the opportunity to record some music on Edison cylinders on behalf of the Biglow & Main company, including this song. The recording of Sankey singing “The Ninety and Nine” features his voice and a piano accompaniment. He sang only the first two stanzas.

III. Assessment

Elizabeth Clephane’s text reflects her gift for storytelling in the way it interprets and expands the original brief parable, including questions by an observer and answers by Jesus. Whereas the biblical parable deals with the idea of seeking and finding the lost sheep, Clephane has interjected the ideas of redemption and the physical cost of reclaiming the lost sheep (the crucifixion).

From a technical standpoint, the irregular text presents a challenge to print in a strophic hymnal format with music, thus also requiring some practice and familiarity by those who sing it. Additionally, the King James language (Thou, Thy, whence, etc.) makes it increasingly less suitable (but not impossible) for use with children or makes it ripe for editorial updating.

Regarding the adoption of the hymn into the gospel hymn genre through the music of Ira Sankey, Mennonite writer Mary Oyer expressed how this hymn and hymns like it have found a place in Christian worship:

“The Ninety and Nine” and many other songs which emerged with the Moody-Sankey revivals owed their strength to their simplicity and folk-like character. The harshest critics found them simple to the point of banality. But Robert M. Stevenson, informed by his knowledge of church history and observation of the church’s experience with gospel songs, said in 1953: “Its very obviousness has been its strength. Where delicacy or dignity can make no impress, gospel hymnody stands up triumphing. . . . Sankey’s songs are true folk music of the people.”[2]

by CHRIS FENNER

for Hymnology Archive

28 October 2020

rev. 6 December 2022

Footnotes:

Ira Sankey, “The Ninety and Nine,” My Life and the Story of the Gospel Hymns (1906), pp. 268–271: Archive.org; in contrast, Frank S. Reader, Moody and Sankey: An Authentic Account of their Lives and Services (New York: E.J. Hale and Sons, 1876), p. 72, says the tune was composed beforehand rather than improvised: “The next day, while seated at a piano in the home of a Christian gentleman, in Edinburgh, Mr. Sankey composed the air for it, and on the following day at the noon-day prayer meeting held in the Free Church Assembly Hall, he sang it for the first time.” Reader’s account of the song’s composition is probably the earliest, published 30 years before Sankey’s.

Mel Wilhoit, “The Birth of a Classic: Sankey’s ‘The Ninety and Nine,’” We’ll Shout and Sing Hosanna (1998), pp. 243–244.

Mary Oyer, “There were ninety and nine,” Exploring the Mennonite Hymnal: Essays (1980), pp. 74–75, quoting Patterns of Protestant Church Music (Chapel Hill, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1953), p. 162.

Related Resources:

James Mearns, “There were ninety and nine that safely lay,” A Dictionary of Hymnology, ed. John Julian (London: J. Murray, 1892), p. 1162: HathiTrust

Duncan Campbell, “Elizabeth Cecilia Douglas Clephane,” Hymns and Hymn Makers (London: A. & C. Black, 1898), pp. 135–136: Archive.org

Ira Sankey, “The Ninety and Nine,” My Life and the Story of the Gospel Hymns (Philadelphia: Sunday School Times Co., 1906), pp. 268–277: Archive.org

Robert Guy McCutchan, “There were ninety and nine,” Our Hymnody: A Manual of the Methodist Hymnal (Nashville: Abingdon-Cokesbury Press, 1942), p. 287.

Mary Oyer, “There were ninety and nine,” Exploring the Mennonite Hymnal: Essays (Scottsdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing, 1980), pp. 73–76.

Mel Wilhoit, “The Birth of a Classic: Sankey’s ‘The Ninety and Nine,’” We’ll Shout and Sing Hosanna: Essays on Church Music in Honor of William Reynolds, ed. David W. Music (Ft. Worth, TX: SWBTS, 1998), pp. 229–253.

University of California Santa Barbara, Cylinder Audio Archive:

http://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/