O happy day that fix’d my choice

with

O DU HÜTER ISRAEL

GUIDING STAR

FESTUS

HAPPY DAY

I. Text by Doddridge

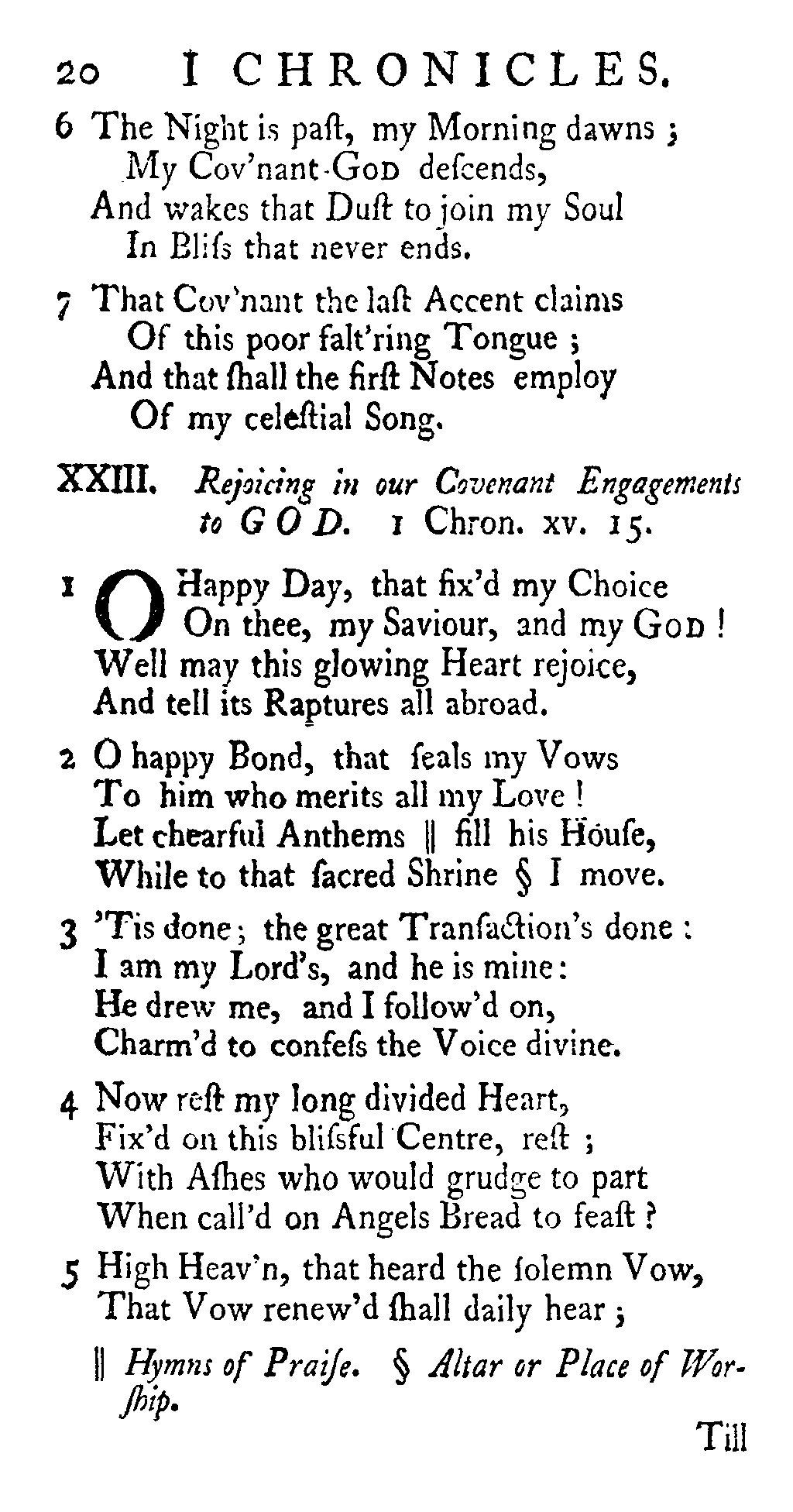

Little is known about the circumstances behind the composition of this hymn by Philip Doddridge (1702–1751). Doddridge had left at least two manuscript collections of his hymns: one now housed at Yale and another kept in the British Library, but neither manuscript contains this hymn. In 1892, historian John Julian offered a similar assessment, saying, “this hymn is not found in any Doddridge MS with which we are acquainted.”[1] It was first printed posthumously in Hymns Founded on Various Texts in the Holy Scriptures (1755), edited by Job Orton (1717–1783), given in five stanzas of four lines, headed “Rejoicing in our Covenant Engagements to God. 1 Chron. xv. 15.” In the second edition (1759), the heading was corrected to say “2 Chron. xv. 15.”

Fig. 1. Hymns Founded on Various Texts in the Holy Scriptures (1755).

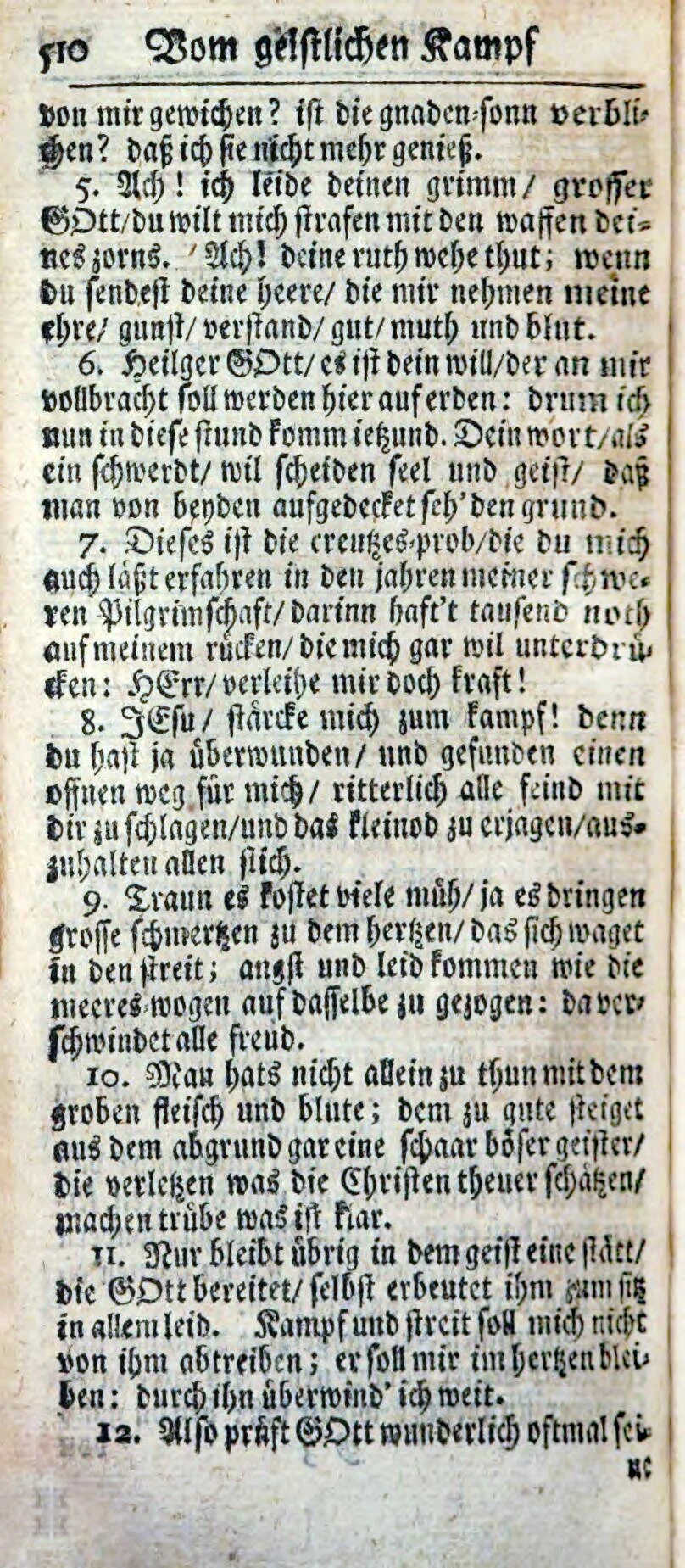

Several years later, one of Doddridge’s grandsons, John Doddridge Humphreys, published a new edition of the hymns as Scriptural Hymns by the Rev. Philip Doddridge, D.D. (1839). In his preface, he lamented what he felt was the “incorrect and unsatisfactory manner” in which Orton had transcribed and edited the hymns. In his rendition of “O happy day,” Humphreys changed two lines at the end of stanza 4. Unfortunately, without a manuscript copy available for comparison, there is no way to know which version of stanza 4 is more faithful to Doddridge’s intent. Julian believed “Orton’s reading has more in common with Doddridge’s usual style and mode of expression than that of Humphreys,” but Humphreys had a stronger claim to accuracy.

Fig. 2. Scriptural Hymns by the Rev. Philip Doddridge, D.D. (1839).

One common alteration of the fourth stanza, “Nor ever from my Lord depart / With him of every good possessed,” is very old, dating at least to 1860. Another alteration of the same lines, “Here have I found a nobler part / Here heav’nly pleasures fill my breast,” is also very old and dates into the 1830s.

II. Textual Analysis

The stated scriptural basis or inspiration for the hymn was 2 Chronicles 15:15, “And all Judah rejoiced at the oath: for they had sworn with all their heart, and sought him with their whole desire; and he was found of them: and the Lord gave them rest round about.” From this, Doddridge incorporated the ideas of speaking an oath (“seals my vows,” 2:1), ardent devotion (see “I am my Lord’s, and he is mine,” 3:2), and rest (4:1–2).

Regarding the hymn’s title, the phrase “covenant engagements” can be found twice in a sermon by Doddridge, “Religious youth invited to early communion,” as in Sermons to Young Persons, 2nd ed. (1737).[2] The sermon was based on Isaiah 44:5, KJV:

One shall say, I am the Lord's; and another shall call himself by the name of Jacob; and another shall subscribe with his hand unto the Lord, and surname himself by the name of Israel.

From this, Doddridge appealed for young Christians to

. . . express their subjection to God, and their readiness to enter into covenant with him, and whatever rites should by him be appointed as the tokens of such a resolution, the text must intimate a cheerful compliance with them; . . . [thus,] under the Christian dispensation, the Lord’s Supper is appointed to such purposes . . . and when we see young Christians presenting themselves at this holy solemnity, and joining themselves to God and his church in it, we may properly say “they subscribe with their hand to the Lord, and surname themselves by the name of Israel” . . . [p. 129].

In recognizing the potential abuse of premature involvement in this sacrament, Doddridge recognized the seriousness of this “covenant engagement”:

I well know, my friends, that the sacred institution I am now recommending is a most awful and solemn thing. I know it was intended, not only as the commemoration of a Redeemer’s dying love, but as a seal of our covenant-engagements to God through him, so that to attend upon it without a sincere desire of receiving Christ Jesus the Lord, and devoting ourselves to him, is a prophanation that renders us, in some degree, guilty of the body and blood of the Lord. I am very sensible, that for any to approach it in so unworthy a manner, is not only in itself a sinful action, but may, in its consequences, prove a snare to their own souls, a stumbling to others, and a dishonour to the church [pp. 130–131].

He also lamented the neglect of this “covenant engagement” among adults:

Judge, I pray you, whether it should be neglected. Judge whether it be a decent thing that when we are sitting down to break and eat bread, and pour forth and drink wine, that we may represent the breaking of Christ’s body, and pouring forth of his blood, and seal our covenant-engagements with him, more than one half of the professing Christians in the assembly should rise, and either leave the place, or withdraw to a distance from the holy table. What is this but to say, “We will now have nothing to do with the memorials of a crucified Saviour?” Will you, my Friends, thus separate yourselves from us? [pp. 134–135].

All of this is to say, his hymn on “Rejoicing in our Covenant Engagements to God” is not so much a celebration of the moment of a person’s salvation, as some commentators have suggested, rather, it was intended a celebration of the commemoration or solemnization of that commitment via a Christian ordinance, especially the Lord’s Supper. The hymn speaks of a “happy bond that seals my vows” and of approaching the “sacred shrine [or altar].” Accordingly, this hymn was adopted into Church of Ireland hymnals in 1873 as a confirmation hymn, and a contributor to The Worshiping Church: Leaders’ Edition (1990) remarked, “Still today it is good for use at confirmations, baptisms, and as a Christian testimony.”[3]

The hymn exudes an unmistakable enthusiasm, seen in words like “happy,” “glowing,” “rejoice,” “raptures,” “cheerful,” and “charmed” (as in Ps. 32:11, 70:4, Hab. 3:18). It is also deeply personal, finding joy in “my Saviour,” “my God.” While the first and second stanzas seem to speak of the ordinance and of being sealed, the third stanza speaks of a “great transaction,” now in the past, which could refer to the salvation/conversion experience, or it could refer to the crucifixion of Jesus. The line “I am my Lord’s, and he is mine” is an allusion to Song of Solomon 2:16. The first two lines of the fourth stanza speak of rest, as in Matthew 11:28 and Hebrews 4:3. The last two lines of that stanza, rarely printed in their original form, convey the idea of gladly exchanging things of the earth for things of heaven. The fifth stanza speaks of daily renewal for the rest of the author’s (or worshiper’s) earthly life.

III. Tune: GUIDING STAR / FESTUS

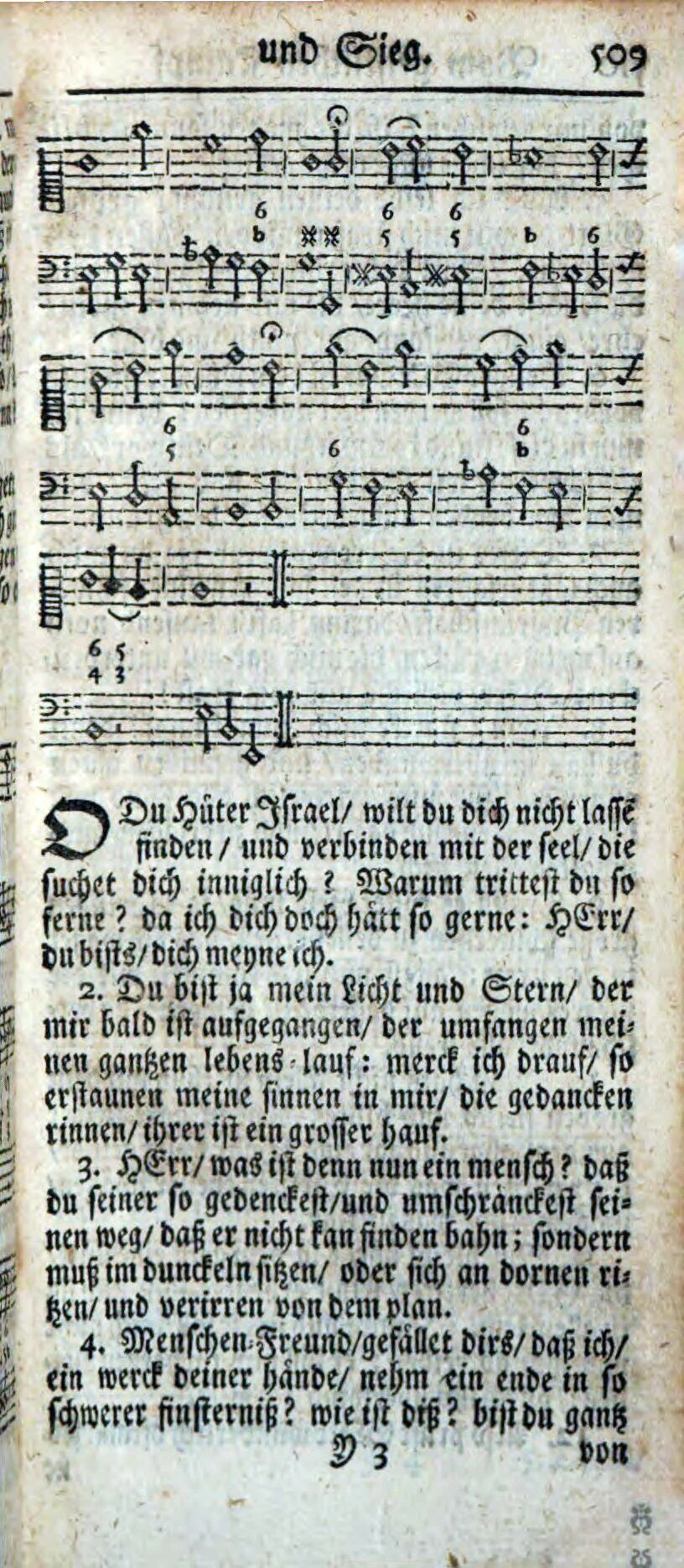

Many hymnals have paired Doddridge’s hymn with a tune called FESTUS, which has its roots in a German chorale tune attributed to Johann Freylinghausen (1670–1739). The tune was first published in his Neues Geist-reiches Gesang-buch (Halle, 1714), melody and figured bass, paired with the text “O du Hüter Israel” (“O you guardian of Israel”) by Johannes Tribbechow (1677–1712). The structure of the tune, judging by the fermatas (and accounting for two missing slurs), is 7.8.11.3.8.8.7, but Tribbechow’s text at times reads like either 7.8.11.3.8.8.7 or 7.8.7.7.8.8.7. In some sources, including Zahn (1891), it is given as 7.8.4.7.3.8.8.7.

Fig. 3. J.A. Freylinghausen, Neues Geist-reiches Gesang-buch (Halle, 1714).

Note: In the critical edition of this collection, the editors regarded the melody as anonymous, without explanation.[4]

An important and popular variant of this melody appeared in Johann Balthasar König’s Harmonischer Lieder-Schatz (Frankfurt, 1738). König flattened the tune from triples to duples, eliminated the passing tones, divided the tune into its component phrases (7.8.11.3.8.8.7), and added a triadic note near the end of the fifth phrase in place of a falling fifth. In English Moravian hymnals, this tune (with a few passing tones added back in) is known as GUIDING STAR.

Fig. 4. J.B. König, Harmonischer Lieder-Schatz (Frankfurt, 1738), p. 313.

When this tune was adopted into the Bristol Tune Book (1863), an editor added a pickup note to accommodate a change to iambic long meter (8.8.8.8), and greatly altered the structure, taking snippets from the middle phrases to create two new inner sections, while keeping most of the first and last phrases.

Fig. 5. Bristol Tune Book (London: Novello, Ewer & Co., 1863).

The connection between Doddridge and FESTUS dates to the middle of the twentieth century, as in Congregational Praise (1951). It is sometimes used by hymnal editors for the purpose of avoiding the added refrain as given in HAPPY DAY, which is not by Doddridge. Also, the music for the stanzas in HAPPY DAY has been parodied (contrafactum) in the secular song “How dry I am” (attributed to Irving Berlin, ca. 1919), thus making it unpalatable to some editors.

IV. Tune: HAPPY DAY

The most common tune setting for Doddridge’s hymn, HAPPY DAY, has its roots in an art song by British composer Edward Francis Rimbault (1816–1876). Copies of “Happy Land” rarely carry copyright or publication dates, but London editions printed by J. Duff have been dated ca. 1837. One early printing by Duff & Hodgson calls the song a “Tyrolienne, sung by Miss E. Honner at the Royal Adolphi Theatre in the Burletta of Rip Van Winkle! Also at the London and Provincial Concerts.” The lyrics to the song are attributed to J. Bruton. The happy land named in the song is “Switzer’s mountain,” possibly in reference to the Swiss alps or to a fictional location. The performance by Honner was advertised in the London Morning Post in October 1839.

Fig. 6. E.F. Rimbault, “Happy Land” (London: Duff & Hodgson, 1939).

The relevant portion of Rimbault’s song is in the first four measures of the vocal part, “Happy land! Happy land! Whate’er my fate in life may be.”

Another possible precursor of the HAPPY LAND refrain is an anonymous text beginning “Whene’er we meet you always say, ‘What the news?’” One stanza (usually printed as the fourth or fifth) contains the following lines:

And since he took my sins away,

And taught me how to watch and pray,

I’m happy now from day to day,

That’s the news! That’s the news!

This hymn can be found as early as 1843 in Hymns for Revival Meetings (London: Houlston & Stoneman), compiled by Thomas Pulsford. It was also printed in The Christian’s Spiritual Song Book (London: W. Brittain, 1845) compiled by John Stamp, and it was quoted in the July 1847 issue of The Mariners’ Church Gospel Temperance Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Magazine (London: Naval and Military Office). The phrase “watch and pray” comes from Jesus at the garden of Gethsemane, asking this of his disciples (Matt. 26:41, Mk. 14:38).

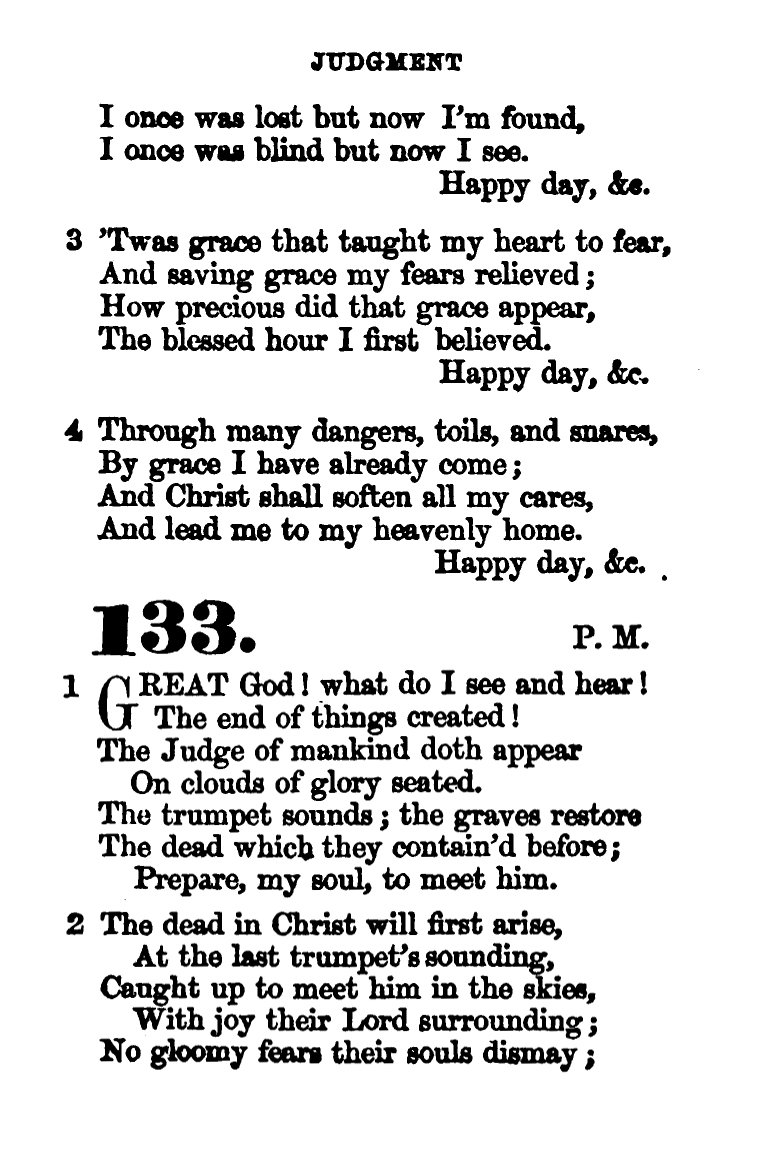

These elements—“Happy Land” and “What’s the News”—seem to have been combined into a new campmeeting refrain beginning “Happy day! Happy day! When Jesus washed my sins away” in the early 1850s. In England, one example of this can be found in The Sunday School Harp (Rochdale: Felix Ashworth & Co., 1854), where it was given with one stanza from “Sweet was the time when first I felt” and three stanzas from “Amazing grace” (both by John Newton).

Fig. 7. The Sunday School Harp (Rochdale: Felix Ashworth & Co., 1854).

The refrain also appeared in Hymns Selected for the Use of the Wesleyan Sunday School, Sherborne (Sherborne: E.M. Kingdon, 1854), without any supporting stanzas and without music.

In the United States, the refrain emerged with music in the Wesleyan Sacred Harp (Boston: John P. Jewett & Co., 1854), named HAPPY DAY, paired with “Jesus, my all to heav’n is gone” by John Cennick, along with “O happy day that fix’d my choice” as a second option. The music was unattributed. The tune for the stanzas (found in the second voice) has no known antecedent, but the tune for the refrain has clear similarities to Rimbault’s “Happy Land” through the first four bars, whereas the rest is new.

Fig. 8. Wesleyan Sacred Harp (Boston: John P. Jewett & Co., 1854). Melody in the second part.

One other early printing demonstrates the wandering nature of the refrain (meaning it was not written specifically for Doddridge’s hymn) and establishes the earliest known printing of a key variant. In Linden Harp (New York: For the Author, 1855), compiled by Lilla Linden, the refrain had a different text, “Happy day, happy day! Here in thy courts we’ll gladly stay,” etc. It was paired with “Preserved by thine Almighty power” by Horatius Bonar. This version of the refrain was reprinted in several other collections, including William Bradbury’s Oriola (1859).

Fig. 9. Linden Harp (New York: For the Author, 1855).

V. Adaptation by Hawkins

In 1968, the HAPPY DAY refrain was famously adapted into a gospel choir piece by Edwin Hawkins, “Oh Happy Day.”

by CHRIS FENNER

for Hymnology Archive

8 September 2022

Footnotes:

John Julian, “O happy day that fix’d my choice,” A Dictionary of Hymnology (London: J. Murray, 1892), p. 834: HathiTrust

Philip Doddridge, Sermons to Young Persons, 2nd ed. (London: R. Hett, 1737), pp. 123–160. PDF

“O happy day that fixed my choice,” The Worshiping Church: Leaders Edition (Carol Stream, IL: Hope, 1990), no. 504.

Dianne Marie McMullen, Rainer Heyink, and Wolfgang Miersemann, Johann Anastasius Freylinghausen Neues Geist=reiches Gesang=Buch, Bd. 2, Tl. 3 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2020), p. 181.

Related Resources:

Johannes Zahn, Die Melodien der deutschen evangelischen Kirchenlieder, vol. 4 (Gütersloh: C. Bertelsmann, 1891), no. 6373.

Erik Routley, “FESTUS,” Companion to Congregational Praise (London: Independent Press, 1953), p. 24.

Richard Watson & Kenneth Trickett, “O happy day that fixed my choice,” Companion to Hymns & Psalms (Peterborough: Methodist Publishing, 1988), p. 398.

Edward Darling & Donald Davison, “O happy day that fixed my choice,” Companion to Church Hymnal (Dublin: Columba, 2005), pp. 775–776.

“O happy day that fixed my choice,” Hymnary.org: https://hymnary.org/text/o_happy_day_that_fixed_my_choice

Françoise Deconinck-Brossard, “O happy day that fixed my choice,” Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology: http://www.hymnology.co.uk/o/o-happy-day,-that-fixed-my-choice