O thou from whom all goodness flows

with

RICHMOND (CHESTERFIELD)

I. Origins

This text and tune, both by Thomas Haweis (1734–1820), were first published in Carmina Christo, Part 1 (London: S. Hazard (Bath), Matthews, and Skillern, ca. 1791 | Fig. 1), in five stanzas of four lines. The collection was dedicated to Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, a lover and patron of hymnody and Methodism who had died 17 June 1791. Haweis was one of her chaplains.

Fig. 1. Carmina Christo, Part 1 (London: S. Hazard (Bath), Matthews, and Skillern, ca. 1791). Melody in the fourth line.

The hymn also appeared in a longer form of six stanzas, text only, in The Reality and Power of the Religion of Jesus Christ Exemplified in the Dying Experience of Mr William Browne of Bristol (Bristol: John Rose, 1791 | Fig. 2). Before his death, Browne was reported as saying, “I have chosen my funeral text and hymn, Remember Me. He hath remembered me, with that favor which he beareth to his own people.” The funeral was 23 October 1791, at which a Rev. Mr. Hey preached from Nehemiah 13:22, “Remember me, O my God, concerning this also, and spare me according to the greatness of thy mercy.”

Fig. 2. The Reality and Power of the Religion of Jesus Christ Exemplified in the Dying Experience of Mr William Browne of Bristol (Bristol: John Rose, 1791).

The following year, in a words-only edition of Carmina Christo, the hymn was given in six stanzas, with some differences from the Browne printing (Fig. 3). This text remained stable through multiple subsequent editions and should be regarded as Haweis’ official version.

Fig. 3. Carmina Christo (Bath: S. Hazard, 1792).

II. Adaptations

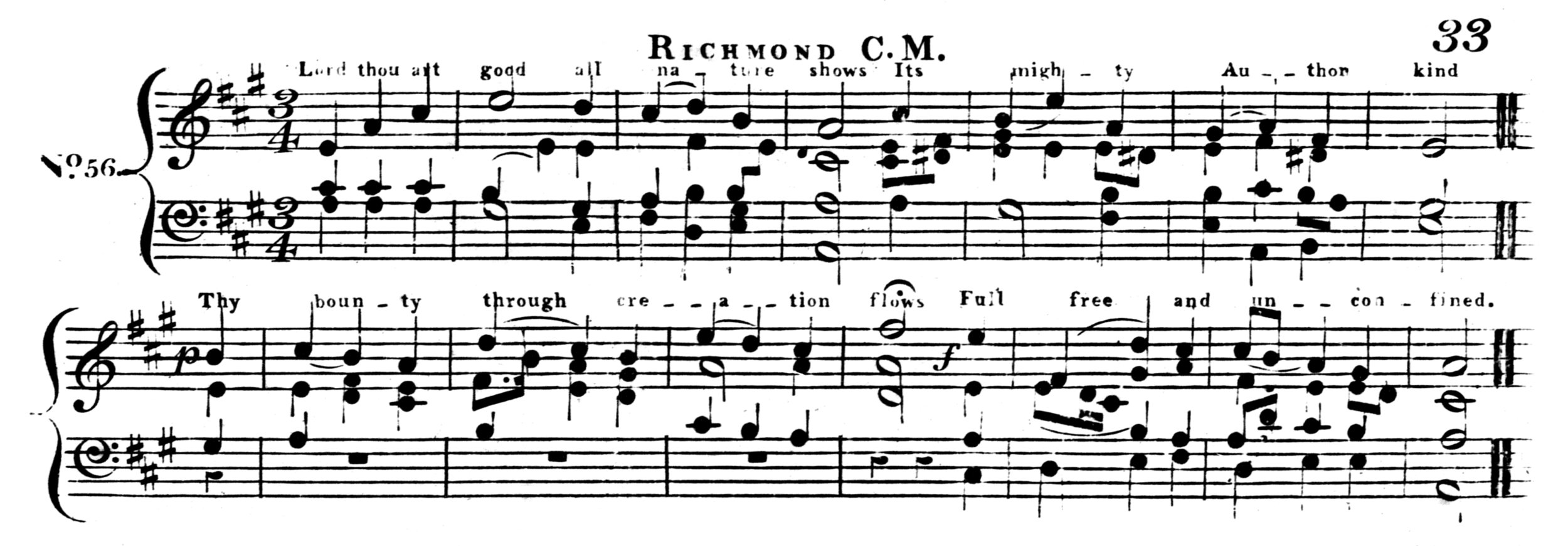

Samuel Webbe Jr. (1768–1843) made two influential changes to the music in his Collection of Psalm Tunes Intermixed with Airs (London: Clementi & Co., 1808 | 1816 ed. shown in Fig. 4). He omitted the fourth musical phrase of Haweis’ tune, which was a florid elaboration of the final line of text and wasn’t necessary or consistent with the rest of the melody. Lutheran scholar Fred L. Precht called Webbe’s version “a notable improvement over the original.”[1] Webbe was responsible for assigning the name RICHMOND. Scholars believe this was a tribute to Rev. Leigh Richmond, a friend of both Haweis and Webbe, who was rector of Turvey, Bedfordshire. The tune is also known as CHESTERFIELD, an alternative name assigned some time after 1820, believed to be a reference to Philip Dormer Stanhope (1694–1773), 4th Earl of Chesterfield, a friend of the Countess of Huntingdon.

Fig. 4. Samuel Webbe Jr., A Collection of Psalm Tunes Intermixed with Airs, 3rd ed. (London: Clementi & Co., 1816).

One notable alteration to Haweis’ text occurred in Thomas Cotterill’s Selection of Psalms and Hymns, 8th ed. (1819 | Fig. 5), which was edited by James Montgomery (1771–1854). In this version, Montgomery made several small changes, mostly adhering to Haweis’ original sense but slightly reworded. The most distinctive change was in the way he made the last line of every stanza to read the same, “Good Lord, remember me.” He also added a seventh stanza, expanding the scope of the hymn to reach beyond death into the throne room of heaven.

Fig. 5. Thomas Cotterill, Selection of Psalms and Hymns, 8th ed. (Sheffield, J. Montgomery, 1819).

This version was repeated in Montgomery’s The Christian Psalmist (Glasgow: Chalmers & Collins, 1825 | Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. The Christian Psalmist (Glasgow: Chalmers & Collins, 1825).

III. Legacy

This hymn was beloved by Henry Martyn (1781–1812), an Anglican missionary to India and Turkey. In his journal for 23 August 1811, he wrote:

The Moollah Aga Mahommed Hasan, himself a Moodurris, and a very sensible candid man, asked a good deal about the European philosophy, particularly what we did in metaphysics, for instance, “How, or in what sense, the body of Christ ascended into heaven?” He talked of free will and fate, and reasoned high, and at last reconciled them, according to the doctrines of the Soofies, by saying, “that as all being is an emanation of the Deity, the will of every being is only the will of the Deity; that therefore, in fact, free will and fate were the same.” He has nothing to find fault with Christianity, but the divinity of Christ. It is this doctrine that exposes me to the contempt of the learned Mahometans, in whom it is difficult to say whether pride or ignorance predominates. Their sneers are more difficult to bear than the brickbats which the boys sometimes throw at me: however, both are an honour of which I am not worthy. How man times a day have I occasion to repeat the words,

If on my face, for thy dear name,

Shame and reproaches be;

All hail reproach, and welcome shame,

If Thou remember me.[2]

The following year, 12 June 1812, he appealed to the hymn again:

I attended the Vizier’s levee, when there was a most intemperate and clamorous controversy kept up for an hour or two; eight or ten on one side, and I on the other. Amongst them were two Moollahs, the most ignorant of any I have yet met with in Persia or India. It would be impossible to enumerate all the absurd things they said. Their vulgarity, in interrupting me in the middle of a speech; their utter ignorance of the nature of argument; their impudent assertions about the law and the Gospel, neither of which they had ever seen in their lives—moved my indignation a little. I wished, and I said that it would have been well, if Mirza Abdoolwahab had been there; I should have had a man of sense to argue with.

The Vizier, who set us going at first, joined in it latterly, and said, “You had better say, ‘God is God, and Mahomet is the prophet of God,’” I said, “God is God,” but added, instead of “Mahomet is the prophet of God,” “and Jesus is the Son of God.” They had no sooner heard this, which I had avoided mentioning till then, than they all exclaimed, in contempt and anger, “He is neither born, nor begets,” and rose up, as if they would have torn me in pieces. One of them said, “What will you say when your tongue is burnt out for this blasphemy?”

One of them felt for me a little, and tried to soften the severity of this speech. My book, which I had brought, expecting to present it to the King, lay before Mirza Shufi. As they all rose up, after him, to go, some to the King, and some away, I was afraid they would trample upon the book, so I went in among them to take it up, and wrapped it in a towel before them; while they looked at it and me with supreme contempt.

Thus I walked away alone to my tent, to pass the rest of the day in heat and dirt. What have I done, thought I, to merit all this scorn? Nothing, I trust, but bearing testimony to Jesus. I thought over these things in prayer, and my troubled heart found that peace which Christ hath promised to his disciples.

If on my face, for thy dear name,

Shame and reproaches be;

All hail reproach, and welcome shame,

If Thou remember me.[3]

by CHRIS FENNER

for Hymnology Archive

8 April 2019

Footnotes:

Fred L. Precht, “CHESTERFIELD,” Lutheran Worship Hymnal Companion (St. Louis: Concordia, 1992), p. 36.

Memoir of the Rev. Henry Martyn (London: J. Hatchard, 1819), pp. 406–407: Google Books

Memoir of the Rev. Henry Martyn (London: J. Hatchard, 1819), pp. 476–477: Google Books

Related Resources:

Charles L. Hutchins, “Thomas Haweis,” Annotations of the Hymnal (Hartford, CT: Church Press, 1872), pp. 46–47.

John Julian, “O thou from whom all goodness flows,” A Dictionary of Hymnology (London, 1892), pp. 850–851: Google Books

Percy Dearmer & Archibald Jacob, “O thou from whom all goodness flows,” Songs of Praise Discussed (Oxford: University Press, 1933), pp. 75–76.

W. Thomas Jones, “RICHMOND,” Hymnal 1982 Companion, vol. 3A (NY: Church Hymnal Corp., 1994), no. 72.

Paul Westermeyer, “CHESTERFIELD,” Hymnal Companion to Evangelical Lutheran Worship (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 2010), p. 2.

“O thou from whom all goodness flows,” Hymnary.org:

https://hymnary.org/text/o_thou_from_whom_all_goodness_flows

J.R. Watson, “O thou from whom all goodness flows,” Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology:

http://www.hymnology.co.uk/o/o-thou-from-whom-all-goodness-flows